In the video for Oneohtrix Point Never’s “A Barely Lit Path,” two crash test dummies ride in a self-driving car. It is night; they are in a forest. They may have been traveling a while, because diversions are in evidence—a chess board, puzzle pieces scattered on the floor. One dummy flips through a lavish edition of Samuel Butler’s 1872 Erewhon, a novel that includes some of the earliest thinking on machine consciousness and artificial intelligence. It’s unclear how or if the dummy reads; though molded in the semblance of human features, its face is smoothly eyeless. Time passes; the dummies clasp each other’s rubbery hands and play rock-paper-scissors. As the car picks up speed, they seem to sense something is awry. One detaches its leg and throws it at the dashboard, but the car cannot be stopped.

This hurtling leg came into my mind reading Rachel Ingalls’ novella, In The Act. Helen’s husband, Edgar, is spending a lot of time tinkering with something in his locked home lab. After he tells her that he needs her to be out of the house while he is working, she sneaks in to see what’s going on:

There was the sofa. And there was a bundle of something thrown on top of it, wrapped in a sheet. She was about to pass by when she saw a hand protruding from one of the bottom folds of the sheet.

She let out a gurgled little shriek that scared her. She looked away then back again. Propped against the edge of the sofa’s armrest was a leg, from the knee down.

It’s all part of an uncannily human-like robot. Helen is unnerved, but comforts herself by imagining that Edgar must be trying to create some sort of super-advanced computerized crash test dummy destined to improve humankind. But of course that is not it—it turns out Edgar is using groundbreaking technology to make himself a hyperrealistic sex robot.

Leg, incoming!

*

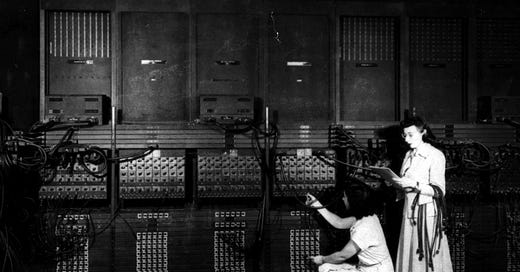

In the beginning, a computer was a person. Computers worked as assistants to alchemists and astronomers, doing calculations and compiling measurements of the skies and stars and seas. By the mid-19th century, computers were often women, who sometimes solved problems as piecework sent by mail. Later, large teams of computers, working in concert, calculated the trajectory of missiles and did the math that detonated the atomic bomb and put humans in space. These groups inspired the development of machine computers, including the ENIAC, built in World War II to automate missile trajectory calculations, and women computers became the first coders, tasked with figuring out the way to get the machines to actually work. It wasn’t long before people starting wondering how to make these machines more human-like in their functions, tracing the weird loop lassoing us all.

Marilyn Wescoff (standing) and Ruth Lichterman (crouching) wiring the ENIAC with a new program. From Mental Floss: “‘There was no language, no operating system, no anything,’ [Kathy] Kleiman says. ‘The women had to figure out what the computer was, how to interface with it, and then break down a complicated mathematical problem into very small steps that the ENIAC could then perform.’ They physically hand-wired the machine, an arduous task using switches, cables, and digit trays to route data and program pulses.” Image from the archives of the ARL Technical Library via Wikipedia Commons.

The MANIAC, (the Mathematical Analyzer Numerical Integrator and Automatic Computer), the machine that gives its name to Benjamín Labatut’s most recent novel, was one of these early mechanical computers.

Labatut’s MANIAC consists of three stories, each a slippery blend of fact and invention. The first, “Paul, or The Discovery of the Irrational,” unravels a crisis of individual despair:

On the morning of the 25th of September 1933, the Austrian physicist Paul Ehrenfest walked into professor Jan Waterink’s Pedagogical Institute for Afflicted Children in Amsterdam, shot his fifteen-year-old son Vassily in the head, then turned the gun on himself.

Ehrenfest, a close friend of Einstein, was bereft. Nazism was ascendent, his beloved son, a Jew with Down’s Syndrome, was doubly imperiled, and the emerging science of quantum mechanics had fractured the world as Ehrenfest understood it:

[He] knew of no way to keep him safe from the strange new rationality that was beginning to take shape all around them, a profoundly inhuman form of intelligence that was completely indifferent to mankind’s deepest needs; this deranged reason, this specter haunting the soul of science … a truly malignant influence, both logic-driven and utterly irrational, and though still fledgling and dormant it was undeniably gaining strength, wanting desperately to break into the world, preparing to thrust itself into our lives through technology by enrapturing the cleverest men and women with whispered promises of superhuman power and godlike control.

The second, “John, or the Mad Dreams of Reason,” is a choral recounting of the startling life of John von Neumann, the person who, perhaps as much as anyone else, is the architect of our current technological reality.1 Through the voices of his colleagues, friends, wives, rivals, brother, and child, Labatut conveys von Neumann’s terrifying brilliance, which led, among other things, to the development of the MANIAC, built at Los Alamos to run the thermonuclear equations needed to build the hydrogen bomb. It later became the first machine to beat a human at chess.2

John von Neumann’s wartime Los Alamos ID badge photo. Labatut uses this von Neumann quote as an epigraph: “You insist there is something a machine cannot do. If you tell me precisely what it is a machine cannot do, then I can always make a machine that can do just that.”

Von Neumann’s capacious, insatiable mind could see things that others’ couldn’t, including a future shaped by artificial intelligence. Labatut has von Neumann’s wife, Klari, describe his vision:

Jansci thought that if our species was to survive the twentieth century, we needed to fill the void left by the departure of the gods, and the one and only candidate that could achieve this strange, esoteric transformation, was technology; our ever-expanding technical knowledge was the only thing that separated us from our forefathers, since in morals, philosophy, and general thought, we were no better (indeed, we were much, much worse) … we had stagnated in every other sense. We were stunted in all arts, except for one, techne, where our wisdom had become so profound and dangerous that it would have made the Titans that terrorized the Earth cower in fear, and the ancient lords of the woods seem as puny as sprites and pixies. Their world was gone. Civilization had progressed to a point where the affairs of our species could no longer be entrusted safely to our own hands; we needed something other, something more.

Labatut’s Klari thinks von Neumann had finally lost the thread: “His analysis made no sense to me and I said as much: There was no evidence for any of this.” But von Neumann is sure this force was coming, and when he asked what it would take for a computer to think, “he said that it would have to understand language, to read, to write, and he said that it would have to play, like a child.”

Lee Sedol, playing AlphaGo in 2016.

The final section of the book, “Lee, or the Delusions of Artificial Intelligence,” deals with what happens when we ask computers to “play.” It reconstructs the 2016 Google DeepMind Challenge match played between Lee Sedol, the best Go player in the world, and AlphaGo, an AI program. The complexity of Go, an ancient game of strategy elevated to an art by its most skilled practitioners, had long thwarted computer programmers who had mastered chess with comparative ease. When Google challenged Lee to play against AlphaGo in a five-game match, Lee was expected to win. Instead, he became a hero for winning a single game. Shattered by the experience, Lee retires from the game:

I don’t see the point. ... Go is a work of art made by two people. Now it’s totally different. After the advent of AI, the concept of Go itself has changed. It is a devastating force.

That devastating force is coming for us all, birthed out of world-destroying bombs, built by people who can’t see the flaw in assuming that just because a thing can be done, it should be done.

*

In the year since I first read THE MANIAC and IN THE ACT, the world has changed. Now, whenever I sit down to type, a little bubble pops up, asking me if I want help “refining” my text. With a few prompts and some editing, I could have saved myself the trouble of trying to write this at all. And reading over what I have written, I can see that it falls short—the transitions jerk and pull; I fail to explain myself. A machine could probably do better.

There are too many things I want to try and cram in—how Microsoft and OpenAI have redefined “artificial general intelligence”—the bogeyman-god computer specter that learns and thinks for itself at a human or superhuman level—as an AI tool that generates US$100 billion in profit.3 Or what it is like to try and edit AI-generated copy, something I have to do more and more, and the way it is a maddening search for a there that is not there, because no actual mind threaded together the arguments. The inane circularity of asking machines to write text to be read by machines. The appalling consumption of energy and water required every time someone skips writing an email or generates a picture of the pope in Balenciaga. (Ingall’s story, written in 1987, nails this—the impulse to reduce miraculous, terifying tools to petty, selfish ends.) I want to share my dumb human certainty that there are no shortcuts to knowledge or art or love or transcendence or care or faith or joy or companionship or community or any of the things that truly matter, that there are only shortcuts to destruction.4

But I will just say that I think both THE MANIAC and IN THE ACT are worth reading—the first, for making too-little-known history come alive, and the second because it is funny as hell, and we need all the laughs we can get as the dummies drive the car toward us, faster and faster and faster.5

Take a moment to scroll his Wikipedia page; be prepared to be awestruck/freaked out by the scope of his work, then request George Dyson’s Turing’s Cathedral: The Origins of the Digital Universe from the library. Labatut credits it as a primary inspiration for The MANIAC, and I found it to be an even more profoundly mind-rattling read.

The computer’s association with games is weird and not a little sinister, I think. Like many, I first encountered this tool, created to facilitate war, as a giant, complicated beige toy for mediocre amusements like Oregon Trail. I was oblivious as to how or why it came to be.

See: https://techcrunch.com/2024/12/26/microsoft-and-openai-have-a-financial-definition-of-agi-report/

Is this where I am supposed to say I am not a machine-smashing Luddite, to signal my fundamentally reasonable nature? Contrary to popular perception, Luddites were not wholly opposed to technology—many used weaving frames and other tools. But what they saw in power looms was the manifestation of a system designed to devalue their labor and enrich the few at the expense of many, and they weren’t wrong.

As I was writing this, another video with a menacing car came to mind: Radiohead’s “Karma Police.” In it, the hapless man who is about to be run down finds the courage to stand up and face the car—and he burns it down. As a bookend to “A Dimly Lit Path,” it conjures a sense of Butlerian Jihad, ha.

i love your brain. SO MUCH.

and yes to having a sense of humor...and to wanting the transitions between paragraphs that are imperfect because they follow the unorganized logic that happens in real time. The path from my brain to my mouth is not automated or perfect, and neither are ways I read or process ideas.

To be clear, I'm also terrified by all of this. But have found my best medicine is just...laughing a lot and doubling down on the secret dumb language I share with the people I love that only makes sense in that context—the inside jokes, the felt experiences, the shorthand I use because it speaks to this bigger feeling that surrounds it all.