Visible mending

When edits are the story.

A brutal edit.

When I tell people I am an editor, they usually have no idea what that means. This is understandable because editing is meant to be invisible. I mostly spend my days in service to someone else’s writing, working as a blurry amalgam of finder, fixer, filter, medium, mediator, therapist, coach, and project manager. No one is supposed to see what I do.

I think this is why I am fascinated by works where editing is obvious—anthologies, collections of letters, selections from diaries, artfully arranged found fragments of text. These are books with ghosts in plain sight, revealed by the shadows of what’s there and what’s not.

Bright fragments, but not a whole.

Helen Garner, HOW TO END A STORY: COLLECTED DIARIES, 1978-1998. This hefty selection of fragmentary diary entries documents twenty tumultuous years in the middle of the writer Helen Garner’s life—a time of professional success, personal struggle, and marital strife. Garner’s attention is capacious and keen, her sentences beautifully precise; her descriptions of weather, of children, of swimming, of people on the bus, in church, or at dinner parties remind me of Vivian Maier snapshots—ordinary life captured with mesmeric, beautiful specificity. These I could read forever, and they could stand alone in a book of their own. But the diary also details Garner’s life and work, and here, I found myself distracted by a sense of something missing.

The diary records what Garner sees, but it does not capture her agency. Her choices happen off the page. Much of the last two-thirds of this volume deals with Garner’s relationship with V., the Australian novelist Murray Bail. There is so much that is ogreish in V.’s behavior from the outset that I was baffled as to why this acutely intelligent, successful, forty-something woman with a rich community of family, friends, colleagues, and lovers, not to mention her own beloved homes, would sacrifice so much to be with him. Inevitably, the relationship fails (he cheats on her with a neighbor), but it takes ten years, 500 pages, and a litany of acutely observed indignities to get there, like the time she shows up at his house to celebrate her birthday and he assumed she would bring the food and cook the dinner, or the time he lectures her about the limits of women’s writing as she scrubs the toilet, something he won’t deign to do. Or the way he insists that she leaves the house every day when he is writing, disparages her work, or protests letting her daughter stay with them when she visits. Besides the long bad dream that is V., there are passages dealing with negative responses to her work—the uproar around her book THE FIRST STONE, which deals with sexual assault charges filed by two young women against the head of their college (Garner thought this was an overreaction), and a friend’s hurt at how she depicts him in a story. Because the diary offers so little context, I ended up reading quite a bit about Garner to piece what happened together.

Anne Enright, in her LRB review of the diaries, writes that “accurate self-observation is not the same as insight.” I’ve never encountered a work that makes that so blindingly plain. It is impossible to know what is in the unedited diaries, but for me as a reader, this edit was both too much and too little. I either needed less, a tighter edit of brilliant descriptions of ordinary life, or more—more context, more depth, more why.

An expert repair.

Elias Canetti, THE BOOK AGAINST DEATH. I read this on a glowing screen, huddled under my striped duvet, very late at night—a cozy spot for cuddling up with this manic scrapbook of death. It is culled from some 2,000 pages of notes, book extracts, one-liners, and news clippings Canetti compiled between 1937 and his death in 1994. Thinking about these reams of material, an infinitude of potential books against death appears in my mind’s eye, but I am grateful to have read this one, selected by an editorial team that included Canetti’s daughter.

The material is organized chronologically. Year after year, Canetti rails against death, his ardor and resistance undimmed, his outrage ever-keen at all loss of life. He finds it unnatural—an affront, an abomination, a theft, a crime, unjust and inhumane no matter the circumstance. (He also defined “survivor” as someone who endures at another’s expense—Joshua Cohen explains that “a classic Canettian survivor is a Hitler, a Stalin, a Hussein, a Putin: a dictator without limits who stoops to every deceit and act of violence to perpetuate his reign, slaughtering his fellow man as a means—and increasingly as the only means—of forestalling his own inevitable mortality.”)

Initially, this struck me as charmingly absurd; after all, aren’t death and life inextricable? But slowly, awe crept in; humility, too. Canetti’s outrage pierces the heart, because he insists there is no small loss: loss is loss. And in his time, same as our own, the impulse to diminish, to calculate, to minimize or balance death and what it represents is always omnipresent. Canetti never succumbs to this. For him, any death is always a total tragedy, an irreparable harm, an attack. Sebastián Sanchéz, in a review for Asymptote, writes, “The Book Against Death represents something of a guerilla campaign: the death of death via a thousand cuts, with the weapon of a thousand aphorisms and ephemera. To read it is to experience a sustained, gradual expansion of one’s conception of what death is, and the role it plays in human life.”

I have found this book deeply helpful in protecting my own sense of outrage from erosion in this era of horrors.

Texts artfully arranged for preservation and enjoyment.

Charles Burchfield, THE SPHINX AND MILKY WAY, ed. by Ben Estes. I first clapped eyes on Charles Burchfield's paintings of slumped houses and ecstatic, vibrational landscapes at an exhibition in New York; though painted long ago, they felt uncannily close to me, and I was jolted to realize he was born in Ashtabula, Ohio, not far from my mother’s family, and grew up in Salem. Most people see Ohio as a nowhere land (it is a place that has been wholly denuded and reshaped by settlers, with old trees and untouched places rare and precious), but there is a beauty here, and Burchfield saw it; Ohio was a landscape that stayed with him. He wrote some 10,000 pages over 54 years of journaling, and the editor Ben Estes has gone through and truffled out an assortment of gems, presented here as fragments alongside reproductions of paintings—Burchfield writing about the shifting sky or the hum of telegraph wires or the sparkle of dewy grass or dandelions:

… it is as difficult to take in all the glory of a dandelion, as it is to take in a mountain, or a thunderstorm.

Ray Johnson and William S. Williams, FROG POND SPLASH, ed. by Elizabeth Zuba. This slim volume is one of the most beautiful pieces of editing I have ever encountered. I go back to it to feel inspired by love revealed in two dimensions— Williams’ clear-eyed, insightful writing about his friend, the collage artist Ray Johnson, and Zuber’s evident care in sourcing, selecting, and arranging these texts, which are pulled from forty years of private emails, letters, published, and unpublished work.

An artful assemblage.

Other books read lately:

TL;DR: faith healers, murderous schoolgirls, zombie travelogues, twisted loves, chalk mountains, historical fan fiction, revolutionary Milton, first-class second-rate authors, a collective novel, conflicted biography, obtuse men, mutant mosquitos, trauma plots, lesser Lispector, bad Cusk, assorted fairy tales.

FEBRUARY

Scholastique Mukasonga, SISTER DEBORAH and OUR LADY OF THE NILE. Picked these books up not knowing what to expect; proverbial socks blown off. One is the twisting, unexpected history of an American who becomes a faith healer in 1930s Rwanda, the other of schoolgirls at an elite Catholic school in Rwanda circa 1980, a secluded environment already thrumming with the currents of bigotry and grievance that will lead to genocide. Electrifying reads; strongly recommended.

Anne de Marcken, IT LASTS FOREVER AND THEN ITS OVER. A zombie lady’s travelogue through an apocalyptic landscape; the image of a one-armed grandmother patiently allowing her zombie grandchild to gnaw the stump is one I won’t soon forget.

Yoko Ogawa, THE HOTEL IRIS. A young woman with a horrible mother drifts into a sordid, sadistic affair with a much older man; a grim read (I prefer THE MEMORY POLICE and THE PROFESSOR AND THE HOUSEKEEPER.)

Michelle White, BLIND FOLLY, OR HOW TACITA DEAN DRAWS. I am obsessed with Tacita Dean’s work, which is why I enjoyed this, even though it is a fairly standard piece of art writing—a bit jargony, a bit repetitious, reaching for something there in the work it fails to capture.

MARCH

Yang Shuang-Zi, TAIWAN TRAVELOGUE. The unlikely love story of two women—a Japanese writer and her Taiwanese translator, ca. 1938—presented as a recovered text with afterword from the women and their daughters. Like TRUST by Hernan Diaz, it over-explains, leaning hard into a vision of the past that seems more wistful and wishful than believable.

Orlando Reade, WHAT IN ME IS DARK: THE REVOLUTIONARY AFTERLIFE OF PARADISE LOST. After teaching PARADISE LOST to a community of incarcerated students, Reade begins to trace how Milton’s poem has shown up in liberation struggles since its publication despite its inherently anti-revolutionary bent. His book focuses on 12 readers of the poem, including Thomas Jefferson, Dorothy Wordsworth, Hannah Arendt, C.L.R. James, and Jordan Peterson. While Reade’s work in prisons and the section on the Haitian revolutionary Baron de Vastey were intriguing, I think I would have preferred rereading PARADISE LOST itself (such a strange work, the way it makes a bureaucracy of Heaven.)

Vicki Baum, GRAND HOTEL. This 1920s smash-hit novel about the denizens of a Berlin hotel was turned into a smash-hit movie and musical; Baum felt dogged by its extraordinary success all of her life. (She described herself as a “first-class second-rate writer.”) I read it in a gulp one night in Paris, sleepless from jet lag. Near the end, there is an odd moment, right in the middle of the action, when everything pauses for a haunting, dirge-like dialogue between a dying man and a naked beauty on the highly specific indignities of their experiences of poverty. I found it worth reading just for that.

The Old School Writers Circle, THE ELEVEN ASSOCIATES OF ALMA MARCEAU. This collectively written cliffhanger feels like it was created by friends having a lot of fun. It is full of interesting ideas—secret cells of older folks working as radio-transmitting spies, mysteries swirling in the Mona Lisa’s sfumato—weighed down by an over-reliance on exposition and skimpy characterizations. Maybe the sequel will help.

Jean Strouse, FAMILY ROMANCE: JOHN SINGER SARGENT AND THE WERTHEIMERS. Reliance on the so-called telling detail is a trap for biographers, but Strouse overcorrects here, larding this chunky biography about Sargent’s personal and professional relationship with a powerful Jewish family with too many details that say nothing. I read it to the end, amazed that someone could do so much research and spend so much time and end up with so little to show for it.

Philip Pullman, CLOCKWORK OR ALL WOUND UP. A well-oiled little tale of deception, desperation, and sinister automatons.

APRIL

Angus Wilson, ANGLO-SAXON ATTITUDES. Academic fraud, midlife crises, hypocrites galore: entertaining (if dude-ly) book about a sixty-something man trying to course-correct after a lifetime of dubious decisions.

Michel Nieva, DENGUE BOY. Mutant mosquito-human runs rampant in dystopian future controlled by virofinance titans; also features a virtual reality game about colonization and vacation resorts in Antarctica, thanks to global devastation. Originally a short story, probably better as a short story, at least for me. Lots of gleeful gore.

Sayaka Murata, EARTHLINGS. A trauma plot pushed to the limit: abused child, murder, disassociation, estrangement, cannibalism! Read after reading Elif Batuman’s profile of Murata in The New Yorker (like sending an alien to profile an alien). I enjoyed the deadpan humor of CONVENIENCE STORE WOMAN, but EARTHLINGS mostly grossed me out.

Clarice Lispector, THE WOMAN WHO KILLED THE FISH. If you have ever dreamed of having Clarice Lispector tell your child a bedtime story, this collection is for you. Four rambling, chatty tales about fatal pet neglect, rabbit detectives, a shaggy dog and a witch, and a dumb hen named Laura.

MAY

Fleur Jaeggy, THREE POSSIBLE LIVES. Intense, shard-like character sketches of Thomas de Quincy, John Keats, and Marcel Schwob with details that lodge in the memory like splinters. I never would have guessed Keats was a fighter.

Rachel Cusk, ARLINGTON PARK. A sour, condescending novel of suburban motherhood.

Sam Wasson, FOSSE. A sprawling biography of the damaged choreographer that counts down to his death; what Fosse got away with boggles the mind.

Natalie Babbit, THE DEVIL’S STORYBOOK. A dapper, trickster Devil attempts to cause mayhem with mixed success in this brief collection of tales.

Joan Aiken, THE WINTER SLEEPWALKER. Read to Hugh at bedtime; I especially enjoyed the story of a tidy sailor who ends up married to Poseidon and is driven mad by the drifting sand that is a constant in their underwater palace. They amicably part ways, and she goes back to the Navy to rise through the ranks, leaving their twins in the care of her mother.

*

Currently reading: PARALLEL LIVES: FIVE VICTORIAN MARRIAGES by Phyllis Rose.

Bookmarked: Jessica Stanley’s new book, CONSIDER YOURSELF KISSED (as a longtime fan of her newsletter, I am thrilled and not at all surprised to see such a rave reaction to her work); all of the books mentioned in this NYR piece by Nathaniel Rich: A SAND COUNTY ALMANAC (time to reread), STORM, THE SECRET OF THE OLD WOODS, THE DROWNED WORLD. Also very intrigued by a title Helen Garner mentions in passing, Edith Sitwell’s PLANET AND GLOW-WORM: A BOOK FOR THE SLEEPLESS.

Blogged: odds and ends / 3.31.2025; flowers for mothers (not medals); imaginary outfit: a rainy saturday walk in paris; the tubs—narcissist.

*

Images:

Fragment of a head of Commodus, ca. 180 CE. National Museums of Liverpool: “Commodus is known to have suffered a 'damnatio memoriae,' and some portraits of Commodus have their faces deliberately removed.”

Byzantine mosaic tesserae. 6th–15th century The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Shigaraki Jar (Tsubo), Edo period (1615–1868). Stoneware with natural ash glaze and gold lacquer repairs. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

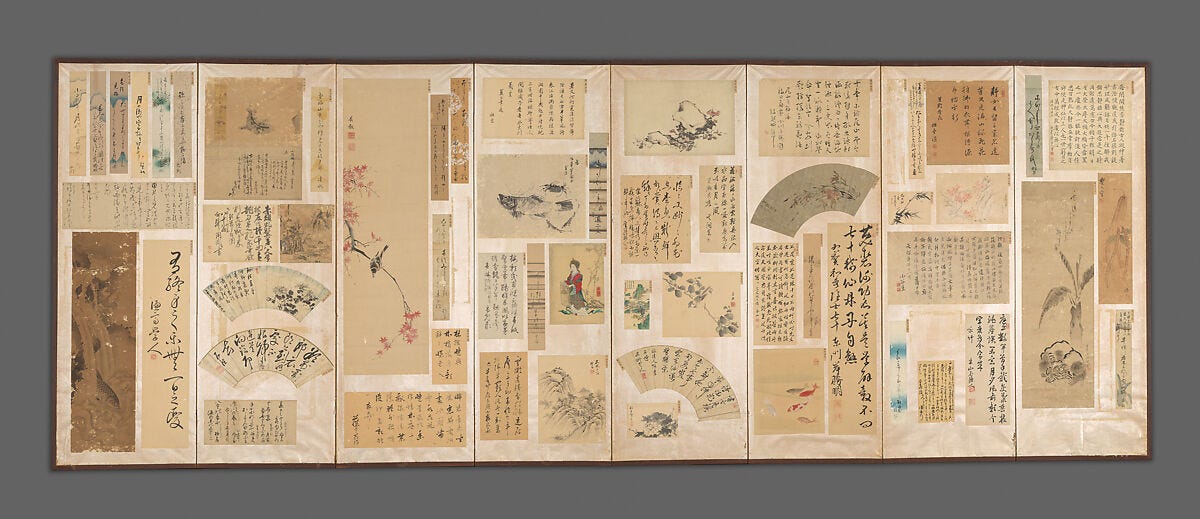

Paintings and Calligraphy by Literati of Iga Ueno, early 19th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Untitled (Memory Jug), undated. Fleisher Ollman.

your reviews are fantastic