"The metal of the knife changes the flavor."

Mushrooms, long ships, assorted disasters, and weird woods.

As I type this sentence, rainbows are dancing across my hands. There’s just enough light filtering through the trees to activate the prism hanging in the window. But even in the moments it took me to write this, the sun moved, and the color is scattering up the wall. I look again, and it is gone.

Time is catching me by surprise. All this to say: I am sorry it has taken me so long to write to you.

In the motley patchwork of my paid occupations, a bright square is editing Mushroom People. It’s a magazine about mushrooms, but also about mushroominess—how encountering the startling, strange, and powerful realities of mushroom lives and ways of being can open fresh pathways to understanding the world around us and our part in it. A second installment is in the works, and I spent some of the summer reading to get my mind in mushroom mode. Hence this short stack:

Anna Lowenhaupt-Tsing, THE MUSHROOM AT THE END OF THE WORLD: I’ve read this book several times now, and each time is like taking a giant hit of oxygen—I come away woozy, exhilarated, a little disoriented, and full of the sense that big, exciting ideas are lurking just beyond the places my mind can reach. Tsing is an anthropologist interested in commodity chains—how materials and labor are extracted and processed through human interactions into that deadly, glittering substance, capital. In this book, she follows matsutake—a mushroom that thrives in “disturbed” forests, places where trees have been cut and harvested—from sites in the Pacific Northwest where it is foraged by an unlikely group of immigrants from an array of South Asian communities, veterans, and other folks living on the margins of society, through the hands of brokers and dealers to Japan, where it is purchased to become a gift. Tsing calls this process “salvage accumulation”:

… living things made within ecological processes are coopted for the concentration of wealth. This is what I call “salvage,” that is, taking advantage of value produced without capitalist control. … “Salvage accumulation” is the process through which lead firms amass capital without controlling the conditions under which commodities are produced.

(Once you start thinking of “salvage accumulation, you see it everywhere, not least in influencers who leverage the gift of attention into a saleable good or, ahem, everything AI, but that is rant for another day, lol.) As she traces the manifold ramifications of the matsutake trade, Tsing explores what it means to look carefully, broadening the lens of what belongs in this story beyond human actions to respectfully engage with living realities of the landscapes involved and the mushroom itself. Entanglement, indeterminacy, precarity, salvage, capitalism, assemblage, and freedom are key themes here, and reading it this time, my attention snagged hard on the idea of assemblage. We live in a time where a lot of voices are raised claiming that “community” is the fix for what ails us, but I think community is maybe too much to ask for. Understanding that we exist in assemblages is perhaps like a more honest place to start:

The question of how the varied species in an assemblage influence each other—if at all—is never settled: some thwart (or eat) each other; others work together to make life possible; still others just happen to find themselves in the same place. Assemblages are open-ended gatherings. … They show us potential histories in the making.

Not an easy read (it is clear but dense with mind) but an invaluable one.

Michael Hathaway, WHAT A MUSHROOM LIVES FOR: Hathaway, like Tsing, is an anthropologist and a member of the Matsutake Worlds Research Group, and this book is a delightfully earnest and wonky artifact of how learning about mushrooms has reshaped how Hathaway understands the world. Ostensibly, it is a look at how the matsutake economy impacts Tibetan and Yi communities, but it’s evident that as Hathaway began to consider what it might mean to really think of mushrooms as equal participants in this exchange, he tumbled into a constellation of trippy rabbit holes tied to the ways that mushrooms live and make worlds. (An enjoyable occupational hazard for anyone who spends time thinking hard about mushrooms.) This is one of those books where you can feel enthusiasm emanating from the page, like sitting next to someone on the subway or in a waiting room who just has to tell you about this incredible thing they just learned. And the book is studded with tantalizing little knowledge breadcrumbs. For example, I can’t wait to read more about the work of Jane Bennett, a political scientist who “argues that the agency of things often exceeds human intentions”—in other words, respecting the ways nonhuman and nonliving things shape the world. She called this “vibrant matter”—I love that.

Pivoting to fiction …

An Yu, GHOST MUSIC: Mysterious mushrooms, a vanished pianist, an enigmatic husband, and a passively oppressive mother-in-law orbit Song An, a melancholic young woman experiencing an increasingly surreal crisis of spiritual dislocation in Beijing. She doesn’t know who she is or what she wants, and the book felt stuck, too, a series of skillfully drafted scenes that missed meaningful coherence.

Karin Tidbeck, AMATKA: Vanja is sent to Amatka, a remote agricultural colony in a bare northern land where mushrooms are grown underground in vast farms. Her job is to study opportunities for marketing new products; it appears that she is part of a totalitarian society shifting towards an embrace of light capitalism, much to the confusion of Amatka’s residents, who do not understand why they might need more stuff. But as she takes up residence in Amatka, she stumbles into happenings that make her question the very nature of reality. Tidbeck conjures an enticingly creeping unease through revelations spun as fine and uncanny as cobwebs, but as the action builds, the story collapses into predictability. A writer’s fantasy dystopia, where nothing matters more than words.

Wearable ghost ship.

Walter Havinghurst, THE LONG SHIPS PASSING: I spent two weeks this summer driving between the Great Lakes to swim in them all (recommended), and I started reading this in Ontario, in Sault Sainte Marie. Havinghurst, a Miami University college professor who worked on the long ships of the Great Lakes in the 1920s, wrote this book in 1942, before the Saint Lawrence Seaway opened a watery highway between the lakes and the sea, tracing how travel and trade on the lakes powered the development, for good and ill, of the United States, pushing people and goods from one place to another. Havinghurst is a poet, and his vibrant, troubled descriptions of the tumult and greed and movement the lakes inspired bring snapshots of the past to glowing life, from the bewildered Jesuits who kept tasting the lakes because they could not believe they were not sea to the season-long journey of giant ships rolled inch by inch along the frozen streets of Ste. St. Marie to reach Lake Superior. The time he reveals is dynamic and blurred, an era of constant, destabilizing shifts. It’s easy to claim that we live in a time of unprecedented change and forget just how long unprecedented change has been the given circumstances of life.

David Grann, THE WHITE DARKNESS and THE WAGER: Grann is a staff writer for The New Yorker who excels at gripping longform nonfiction narratives which often get turned into books. This is probably the third time I’ve read THE WHITE DARKNESS—it is the story of Henry Worsley, a soldier turned polar adventurer who venerates Ernest Shackleton, and his attempts to cross Antarctica. It’s a devastating and subtle illumination of the way obsession can blind a person to knowledge, because for all of Worsley’s veneration of Shackleton, he cannot emulate him. THE WAGER uses the story of a 1740 shipwreck to unspool a series of fascinating historical gobbets, like the appalling number of trees needed to make one ship (they were floating forests), the absolute savagery of life at sea, the predictable but still astonishing callousness the British exhibited toward local peoples (even when those people were offering them a lifeline), the sophistication of 18th-century personal press propaganda, and a generally gobsmacking colonial cultural commitment to bureaucracy. At times, the incredible level of detail and research felt a bit like a narrative drag, but it was still a startling and entertaining read.

WEIRD WOODS: TALES FROM THE HAUNTED FORESTS OF BRITAIN, ed. John Miller, and EVIL ROOTS: KILLER TALES OF THE BOTANICAL GOTHIC, edited by Daisy Butcher: These two titles are part of The British Library’s series of thematically organized spooky stories; lots of carnivorous plants and creepy trees. I didn’t love the way the pedantic micro-intros to each tale interrupted the story flow, though—mood murderers.

I had seven more books listed here to write about (ye gods!), but this is plenty long already. Look for an upcoming installment on FRANNY AND ZOOEY, SUMMER, I AM HOMELESS IF THIS IS NOT MY HOME, THE WIZARD OF WEST ORANGE, BEAWOLF, THE SWIFTS: A DICTIONARY OF SCOUNDRELS, and HOWL’S MOVING CASTLE.

Currently reading:

PARTY OUT OF BOUNDS: THE B-52S, R.E.M., AND THE KIDS WHO ROCKED ATHENS, GEORGIA; THE EXTINCTION OF IRENA REY

Bookmarked:

CORAL DICTIONARY VOL 1., 2019-2022; NOVEL EXPLOSIVES; WHAT HAPPENS BETWEEN THE KNOTS?; THE STRANGE LIFE OF OBJECTS; QUANTUM LISTENING.

Blogged:

The Beths, “Expert In a Dying Field”

*

Images:

Ramon Casas, Jove Decadent, Despres del ball, 1899. Oil on canvas. Museu de Montserrat.

Lithograph from M. E. Descourtilz’s Atlas des Champignons, 1827. Via The Public Domain Review.

Micro sculpted ship ring, possibly Dutch, ca. 1780. Via Classical Gem Hunter.

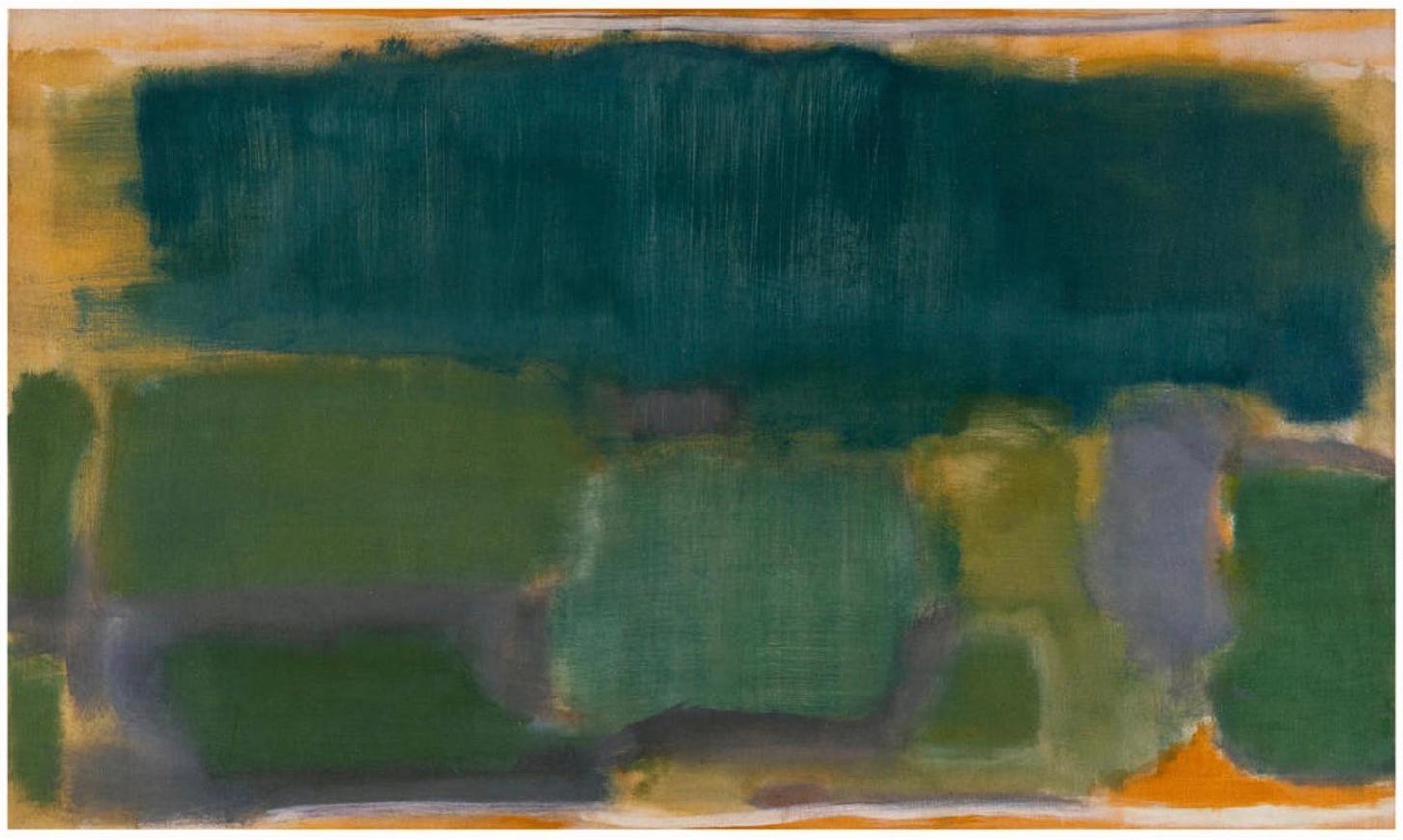

Mark Rothko, N. 32/N. 4, 1948. Oil on canvas.

Post title from THE MUSHROOM AT THE END OF THE WORLD.

Thank you for this newsletter-- I find your writing to be dense in the most luxurious way. (I think density is unfairly used to describe a lot of bad academic writing-- to be clear, this isn't my meaning at all!) 🍄