Been spending time reading books that make me feel like a dolt; it feels good to walk right up to the crumbling edge of my limited intelligence and peer out at the vast everything, perceptible to me only as vague blobs and fuzzy shapes, and realize how little I understand about anything. Wholesome content!

Tarjei Vesaas, THE BIRDS. Or: the addition of 1 to 2 sums to zero.

Mattis and his sister, Hege, live in a shabby cottage in a remote Norwegian village. She supports them both by knitting sweaters because even menial jobs challenge Mattis. He is painfully aware that he is different from other people; in the village, they call him Simple Simon, a fact that mortifies him. But as much as he wishes to connect, something breaks down whenever he tries to communicate, and what he feels remains trapped inside, whether it is his deep wonder at the beauty of a woodcock or his touching love for his sister. Hege’s consistent care for Mattis gives his fragile world stability. But when a stranger arrives and Hege falls in love, Mattis is pushed to the side. Vesaas’ quietly beautiful, subtle, troubling tale reveals the tragic costs care can exact, both for Mattis and for Hege, and the deep human need to be seen, to sit somewhere close to the center of another heart.

Percival Everett, TREES. Or, the incalculable sum: 4,400 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 …

There is a vast churning puke-green sea of lethally boring professionalized writerly discourse aswirl online and in drab conference rooms on subjects such as "genre” and “branding” and “craft” and “hybridity” and, yawn, I’m bored just typing this. It’s a windy inefficient way to say that Percival Everett ignores all of that and writes whatever he wants however he wants and reading anything by him is like getting to sneak out of a sad drab literary Kansas into a technicolor world with whole other realms of possible stories and thematic combinations defying rigid, market-oriented delineations. This is a murder mystery, a romp, a zombie flick, a buddy comedy, a mood, a curse, a vengeance, an invocation, a warning. It is hilarious and gross and broad and specific and shocking and serious. It is a book about racial terror, about Black vengeance and white culpability. It is a book that zanily and grimly imagines true reparations for lynching.

The crime, the practice, the religion of it, was becoming more pernicious as he realized that the similarity of their deaths had caused these men and women to be at once erased and coalesced like one piece, like one body. They were all a number and no number at all, many and one, a symptom, a sign.

Cormac McCarthy, STELLA MARIS. See also: Goedel’s incompleteness theorems.

Alice is (supposedly) a brilliant twenty-one-year-old mathematician who has checked herself into Stella Maris, a mental institution. Her brother, a failed physicist and race care driver, is in a coma and the doctors want her to pull the plug, but she can’t. Circle back to that supposedly: Alice is not really a person so much as pure mind, a vessel for ideas, and the book unspools as a dauntingly intense meditation on the limits of knowledge, specifically mathematical knowledge, which encompasses meanings mere language cannot. It is also about the tension between the conscious and the unconscious and the ways that humans remake the world we apprehend—through words, which deform all they come in contact with, but also through the advanced mathematics that enable both new ways of seeing and new pathways of destruction (Alice’s father was part of The Manhattan Project). And then there are strange miracles, like the invention of the violin. Is this a novel or a philosophical dialogue? A conversation between a troubled patient and a plodding therapist, or something more like a Greek myth recast for our therapy-infected age, the confession of a fallen minor divinity granted access to the ends of knowing, haunted by a glimpse of hell, the legacy of a godlike father, and an incestuous love for a brother seemingly lost, though he will return from the dead in future she cannot see? Most of this book sat at the far edge of what I can apprehend, but it was exhilarating to read, to see the light and shadows cast by a more brightly burning mind. (Speaking of: Joy Williams’ review of this book and its companion, THE PASSENGER, is an illuminating read.)

Yoko Ogawa, THE HOUSEKEEPER AND THE PROFESSOR. Refer to: the unexpected resonance of amicable pairs.

If STELLA MARIS is about the limits of mathematics in apprehending the meaning of everything, this is a story about numbers creating a pathway to something incalculable. The housekeeper and her ten-year-old son are drawn to the housekeeper’s latest client—a mathematics professor whose short-term memory lasts only 80 minutes. His love of numbers is a strange attractor, illuminating the world in ways the housekeeper and her son unexpectedly find irresistible, as they are beguiled by primes and the elegance of factorials, and the deep kindness and courtesy of the professor himself. (Charmingly, the Professor calls the boy “Root” because his square head reminds him of the square root symbol.) This is a beautiful, beautiful idiosyncratic book, a pure pleasure to read, even if the kid-level math problems sometimes tripped me up. Ogawa’s interest in memory fascinates me; the other book of hers I’ve read, THE MEMORY POLICE, is even more intensely focused on the ways memory, and its loss, make and unmake our world. (It was one of the three books that seemed to me to capture how I experienced the pandemic, along with Susanna Clarke’s PIRANESI and Marlen Haushofer’s THE WALL.)

I looked at the Professor’s note again. A number that cycled on forever and another vague figure that never revealed its true nature now traced a short and elegant trajectory to a single point. Though there was no circle in evidence, π had descended from somewhere to join hands with e. There they rested, slumped against each other, and it only remained for a human being to add 1, and the world suddenly changed. Everything resolved into nothing, zero.

Euler’s formula shone like a shooting star in the night sky, or like a line of poetry carved on the wall of a dark cave. I slipped the Professor’s note into my wallet, strangely moved by the beauty of those few symbols.

Alec Wilkinson, A DIVINE LANGUAGE. Or: attempt to solve for the limit.

This presents as a crusty-old-man stunt book: 65-year-old who barely squeaked through Algebra II decides to take a year to learn algebra, geometry, and calculus, with an assist from his mathematician-professor-niece. Quickly, though, it shifts into something more profound: not only an elegant survey of mathematical history and meaning that made me want to read twenty more books about various mathematical disciplines and theories but also a profound, inadvertent reckoning with finding the limit of your capabilities and choosing to stay in that space, knowing that however hard you work, you will only ever grasp the simplest part of what’s there to be discovered.

Currently reading: LITTLE DORRIT.

Bookmarking: A DARK WILDERNESS: BLACK NATURE WRITING FROM SOIL TO STARS; THE FATAL EGGS; TROUBLE WITH LICHEN.

Blogging: Odds and ends 2.8.2023; imaginary outfit: wild things; hearts.

*

Images:

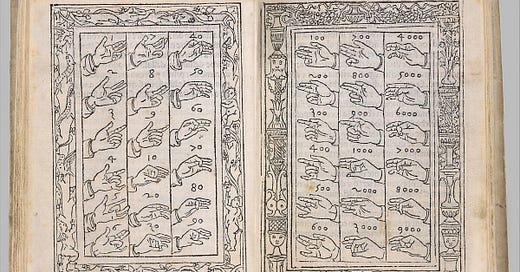

Woodcut illustration from Filippo Calandri’s De Arithmetica.

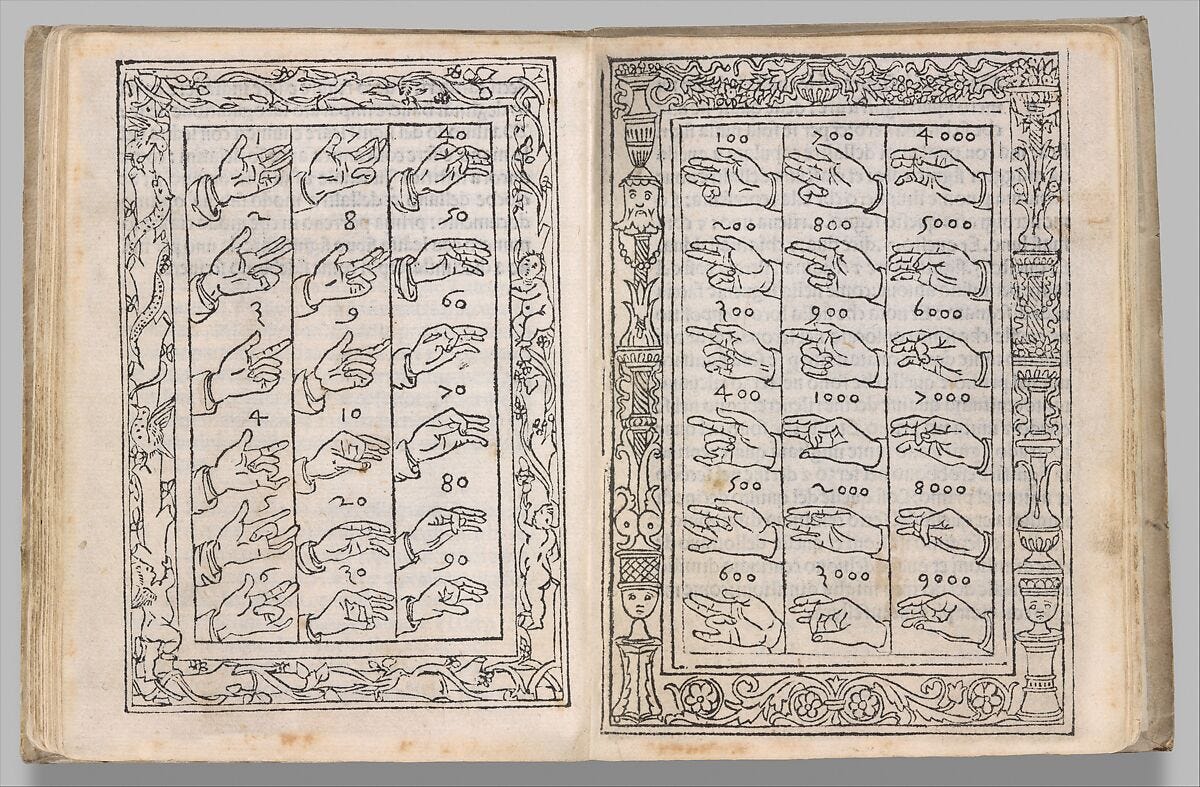

Albrecht Durer, Melencolia I, 1514. Per The Met:

The winged figure in Melencolia I has inspired many readings over its long history, although her ties to mathematical knowledge are often highlighted. Many of her accoutrements are borrowed from medieval and Renaissance allegories of geometry that personify it as a woman working at a table surrounded by tools. Perhaps most notably, a truncated rhombohedron looms large in the middle distance, dividing the foreground—a scene replete with the detritus of measurement—from the limitless background of a placid sea that vanishes into the horizon, presumably the type of natural territory the geometer purports to measure.

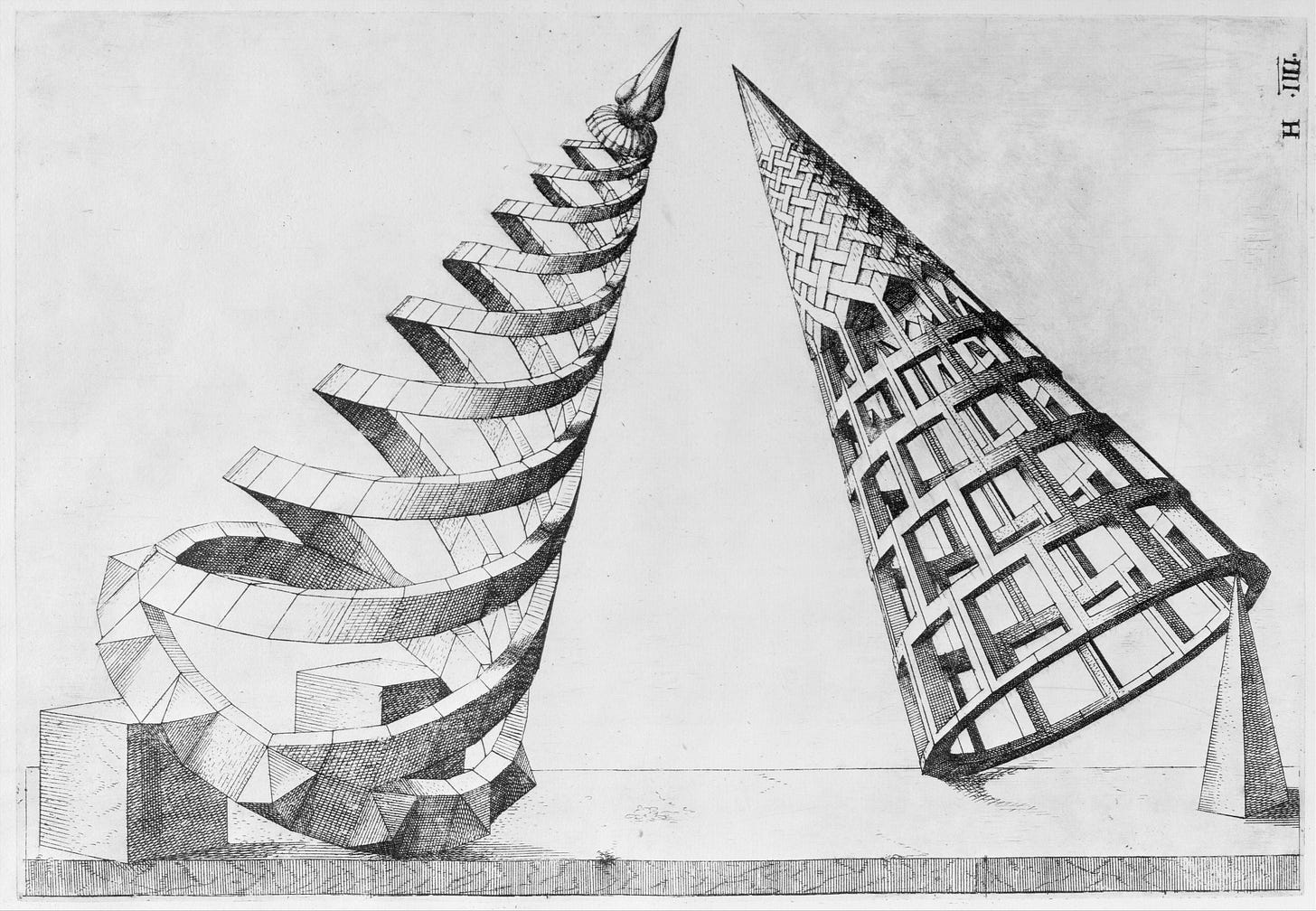

Engraved illustration from Perspectiva Corporum Regularium, 1568, by Jost Amman, after Wenzel Jamnitzer (German, Vienna 1507/8–1585 Nuremberg)