Marking time

Books by clockmakers and books by writers.

Ah, summer: I am in the garden every day, smashing the Popillia japonica using my roses for their bacchanals. The rocks edging the beds are spattered with iridescent carcasses.

But when I am not busy killing beetles, parenting, or earning money, I read.

A perfect ensemble for my murderous garden activities: a gown bedecked with beetle-wing cases.

Lucy Ives, LIFE IS EVERYWHERE. Stashed in the less-popular corners of encyclopedic museums, usually somewhere near the Dresden shepherdesses, shell-shaped salt cellars, and silver-chased vinaigrettes, you find guild pieces. These are fantastically overcomplicated, technically astonishing, and functionally impractical items, like boxy clocks and massive padlocks, some long-dead artisan made to scrabble admittance to a guild—the group that controlled access to materials, opportunities, and markets for a specific craft. Anyway, this book is a 21st-century guild piece—a whiz-bang objet crafted to impress other writers. It is composed mostly of the items in one forlorn grad student’s bag: two novocaine-girl fictions-in-progress (i.e., that weirdly pervasive genre centering youngish/immature women, usually grad students or academics, oppressed by their privileged 21st-century lives), a rejection letter from a publisher, a bill, pompous academic papers, etc. (The structure is a literal riff on Ursula K. LeGuin’s “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction.”) There are pages and pages of impressive sentences, interesting-ish ideas, and convincing spoofs of repulsive genres, all oriented toward a very of-the-moment crisis mash-up of Me Too incident, overlooked/misread works in the archive, hidden queer histories, sad grad students, miserable academia, and the Power of Fiction. Look, I love literary shenanigans—that’s why I picked up this book, and that’s why I slogged through it, hoping there would be some sort of writerly legerdemain that made it worth it. Alas. Ives is a dauntingly bright human. But reading a performance of brilliance is not the same as reading a brilliant novel.

I was so aggravated by this book and its extravagant squandering of Ives’ talent and my time that I had to read five novels, one Agatha Christie, and a slew of Peter Wimsey mysteries to recover my readerly equilibrium.

I mean, it’s cool? But it is a lot for a clock.

Alan Hollinghurst, THE LINE OF BEAUTY. This book reminded me of an English garden—a meticulously, artfully, and seductively controlled presentation of nature. There is beauty in abundance—beauty of form, beauty of line, beauty of attention, and, dear god, so many, many beautiful sentences. AND there is a plot! Its very traditional approach—focused on characters and what happens to them, with a big crash of action at the end—makes plain that form is well and good, but what’s essential for novelistic greatness (and all greatness is radical) is astute attention, inimitable skill, and having something meaningful to illuminate. (Just that, ha!) This is a story in three acts, set in the Thatcherite England of 1983, 1986, and 1987. Nick Guest—a young gay aesthete with a thing for Henry James fresh out of college—is enmeshed with the Fedden family through his friendship (and crush) on Toby, their golden son, and his protective relationship with Catherine, their troubled daughter. The Feddens move in rarified social circles—there’s a house in Notting Hill; Gerald, the father, is an ambitious and opportunistic Conservative member of Parliament in emotional thrall to Thatcher, and Rachel, the mother, is part of an extravagantly wealthy, titled Jewish family. True to his name, Nick is a guest in the Feddens’ world, occupying a permanent-seeming yet precarious position that depends on his discretion and utility. His sexuality is accepted as long as it is unstated and unseen, but when his personal life collides with the Feddens, disaster ensues. As someone whose childhood and youth happened during the evolving terror of the AIDS epidemic, I had horror in my heart almost from page one because the reader experiences Nick’s developing sexuality and sensual freedom knowing the future he doesn’t see coming. It’s the rare book I finished and wished I could read again and again, but each time told from the perspective of a different character, because they are all that compelling. If you are looking for a subtle, satisfying, mesmerizing read, this is it.

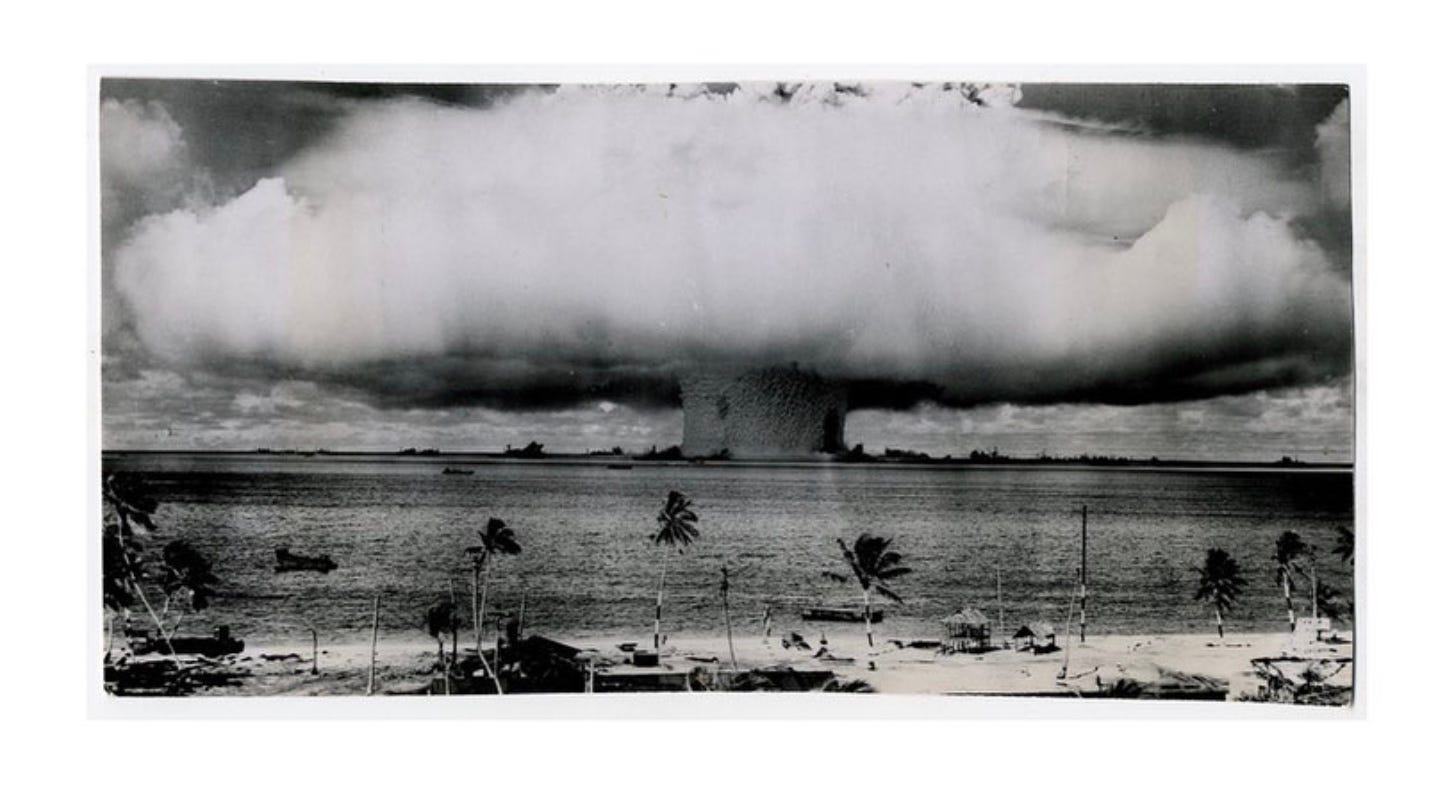

Cormac McCarthy, THE PASSENGER. Ugh, this newsletter is already terrifyingly long, and we haven’t even gotten to this book, which has absolutely colonized my brain. While STELLA MARIS, its sister, is a focused encounter with the limit of human intelligence, THE PASSENGER is a study of fragmented existence in what comes after, of lives in an unfathomable world. Alice Western, the center of STELLA MARIS, appears here in flashbacks as a young teen encountering her grotesque hallucinated vaudeville, led by The Thalidomide Kid. Her brother, Bobby, meanwhile, is living with her death. He survived a catastrophic race car crash and works as a salvage diver, cobbling together a tenuous existence in 1980s-era New Orleans populated by a loose confederation of misfits and outcasts. It is a grubby world streaked with the uncanny and sinister—plane crashes and missing bodies, federal agents and JFK conspiracy theories—but the mysteries never resolve; they mutate. That Bobby’s father helped build the atom bomb, and that Bobby and Alice loved each other too much are the two facts of his life. He goes down, again and again, into murky depths, looking to recover something, looking for Alice. But what’s there cannot be recovered. The scenes in this book are so intensely cinematic and potent that I feel like they put actual cinema to shame—I am not sure mere images could be as vivid or expansive as what McCarthy creates here and in the space between these two books. Reading this was like handling a snake, an encounter with incredible, unsettling, absolute aliveness. I couldn’t put it down. (Sidebar: I would like to read a brilliant essay on the ways the atomic bomb is percolating back up into cultural consciousness now … these books, of course, but also WHEN WE CEASE TO UNDERSTAND THE WORLD (another book loved), “Asteroid City,” and “Oppenheimer.”)

Bombs away.

Jenny Erpenbeck, KAIROS. When Katharina learns that Hans has died, she pulls down a box of memories tracing the origins of their relationship, which began in a city divided by a wall that would not stand much longer. Perhaps it is not surprising that a romance between a nineteen-year-old woman and a middle-aged man curdles into something toxic, but the peculiar bitterness of the poison is a product of its place and time—in the sense of a grand experiment ending, in the loss of faith that something better was possible, in the horrible compromises and betrayals made in the name of ideals. I did not think this book attained the level of THE END OF DAYS, which, to me, is a peak life reading experience, but it was an engrossing, revealing encounter with a moment in time echoing through our own.

Edith Wharton, THE MOTHER’S RECOMPENSE. A fusty title for a sharp, sharp book. Here is a snippet from Ethel W. Hawkins’ review for The Atlantic in 1925:

In many respects The Mother’s Recompense is Mrs. Wharton at her best. It has the distinction of style, the wit, the emotional intensity, and, under the sardonic manner that repels the sentimental reader, it has the deep preoccupation with the ethical problem, and the sense of the ideal immanent in the actual, even in the shabby and shoddy actual, so characteristic of her fine art.

As a young woman, Kate Clephane left her husband for another man, and, as a result, was cut off from her baby by her husband and his family—a loss she has carried for twenty years. In the time since, she led a blameless life in exile, except for one slip—a love affair with a much younger man. Then, WWI happened, and the world changed. Kate finds herself contacted by her daughter, an independent-minded, fabulously wealthy young woman who wants a relationship and to share all that she has. As Kate steps into this new life, she experiences the disequilibrium of seeing that the circumstances of her life were a fluke of timing and feels the touch of constraints that drove her to leave. Then, her past becomes something she cannot escape. Wharton, exquisite narrative sadist, appears to create an avenue for Kate to have it all, but being who she is, can she take it? This is a shattering portrait of a woman caught in a changing culture. Why we are not all reading Wharton all the time, I do not know.

Alejandro Zambra, THE BONSAI. A book about lovers who lie to each other about what they have read and what they are writing and the small cast of friends who cross their paths. There is also a bonsai tree (symbol alert!) and oodles of literary references. Many lines made me laugh out loud, but it is very much the sort of book a clever young literary dude would write to amuse and impress other clever literary people. Amusing enough pool read, though.

Agatha Christie, THE AFFAIR AT STYLES (the first Hercule Poirot mystery). Stiff as a celluloid collar with a teeter-totter plot: He’s guilty! No, he’s not—wait! Yes, he is! All the classic Christie elements are here—tormented pretty ladies, weaselly husbands, family secrets, burned letters, little grey cells—but this one is not as highly burnished as her later work.

Dorothy L. Sayers, WHOSE BODY? / CLOUDS OF WITNESS / THE UNPLEASANTNESS AT THE BELLONA CLUB / HAVE HIS CARCASE / BUSMAN’S HONEYMOON /LORD PETER VIEWS THE BODY. I am fascinated by Sayers, who seems to be a writer who somehow was both trapped and liberated by the genre she wandered into and the character she created. Maybe that is what makes the Lord Peter stories so toothsome. Sayers is less interested in who did it than what it means to want to know who did it and the moral ramifications of getting into other folks’ business. (Lord Peter, the OG true crime enthusiast.) Then, the relationship between Peter, bon vivant gentleman sleuth of unsuspected depths coping with what is essentially PTSD from WWI, and Harriet Vane, the ambitious, independent murder mystery author he rescues from a poisoning conviction, gets into the absolute tangle of love, sexual attraction, obligation, career, gendered expectations, what it means to truly be a partner, and what it means to commit to a calling in a way rare to encounter. So while these books offer ingenious plots, satisfying denouements, Jazz Age fizz, and sophisticated literary references, what I love most is the other, unexpected notes they hit, too.

Kid stuff:

Beverly Cleary, BEEZUS AND RAMONA / RAMONA THE PEST / RAMONA THE BRAVE / RAMONA AND HER FATHER / RAMONA AND HER MOTHER / RAMONA QUIMBY, AGE 8. My kid enjoyed listening to me read these, but I found the aggressive averageness of the Quimby-verse a bit of a bummer to inhabit. That said, Cleary wrote these books over 40 years—the first one was published in 1955 and the last in 1999—and the shifts in parenting culture are amusing to clock. Four-year-olds playing at the park unsupervised! Kindergarteners walking whole blocks to school on their own! Dads bowling and SMOKING CIGARETTES in the house! Moms spending all of their time cleaning, cooking, parenting, and working—oh wait.

E. Nesbit, THE STORY OF THE TREASURE-SEEKERS. In this book, written in 1899, the five plucky Bastable children hatch improbable plots to improve their family fortunes, leading to scrapes and shenanigans. It is narrated by a Bastable child who affects anonymity (figuring out who it is delighted us). What a strange, strange person, Nesbit—co-founder of the Fabian Society (a.k.a. ardent socialist) with an extraordinarily convoluted personal life (it inspired A.S. Byatt’s THE CHILDREN’S BOOK) who wrote fictions where (spoiler alert) everyone ends up comfortably wealthy.

Jon Klassen, THE SKULL. Klassen is dominating the micro-niche of creepy horror stories for the six to eight set. (My kid was so freaked out by the eyeball alien in THE ROCK FROM THE SKY that after we read it, we had to hide it on the back of the bookshelf for two years.) In this droll and deadpan tale, Ottilla is on the run; from what, who can say? She finds a house inhabited by a skull; it is chased nightly by a headless skeleton. With a bucket, a rolling pin, some tea, and some nerve, she finds her way to a happy—or happy enough—ever after.

Currently reading:

SUMMER; THE COMPANION SPECIES MANIFESTO; and LICHENS: TOWARD A MINIMAL RESISTANCE.

Bookmarked:

THE MILLSTONE, because of this Backlisted episode, which features several absolutely brilliant clips of Drabble talking, and THE WATER BABIES, on Drabble’s recommendation.

Blogged:

*

Images:

Beetle-wing dress worn by Lady Russell, Jane Eliza Sherwood (1797-1888). The Wilson.

Augsburg astronomical table clock, second quarter 17th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Press image of an atomic bomb test explosion in the snapshot collection of Billy Parrott.

I recently finished When We Cease... and found it has really stayed on my mind. To describe that math in a translatable way is so impressive! I'm in New Mexico and so the nuclear world is always close by and top of mind for many of us-- people are still developing cancers from the initial explosions, so it's a quite bodily and physical thing. The national Oppenheimer hype has been interesting to watch from here.

Happy to know I've been sharing a cultural wavelength with you - I'm currently reading both Wharton and dabbling in Agatha Christie books. I'll be adding The Mother’s Recompense and The Affair at Styles to my list, among others you've mentioned. I also agree we should all be reading Wharton all the time - at the moment I'm reading her collection of short stories, Ghosts.