Lost in dreams

Jewel-like non-essays, haunted poems, an antic novel, and a fraught biography

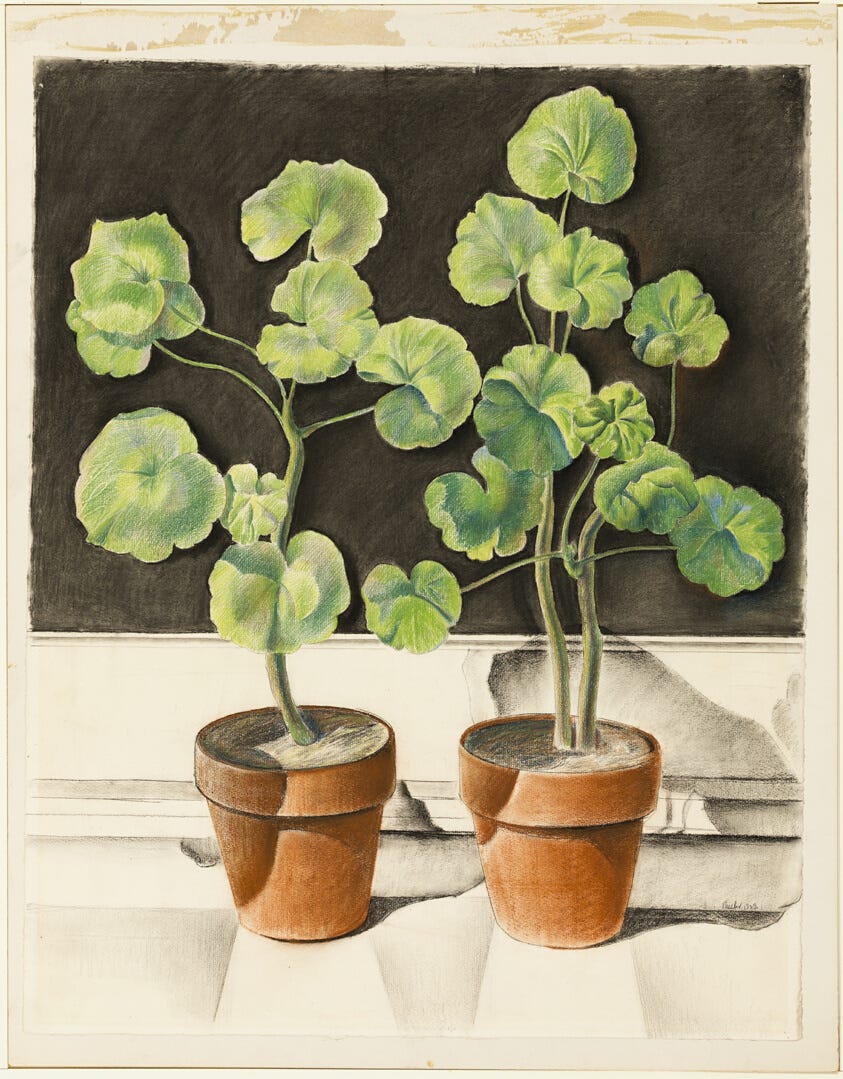

In a fog of February malaise, I missed watering the geraniums in my office last week, and now their leaves are hanging like limp flags of surrender. I gave them a good drink today and the sun finally came out, so I’m hopeful we’ll both revive soon.

I’ve been reviewing pitches for a new project on sound, which is like getting to eavesdrop on someone else’s dream and pass judgment: yes, this one will come true. Patterns always emerge—I think writers would be shocked to see the sameness in so many personal stories, so many original ideas, so many lyrical voices. (Alice Oswald’s description of lyric as a closed space vs. epic as an opened space “propel[ing] you beyond the voice, beyond the mind” crystallized for me what I am chasing as a reader and what I dislike in lyrical writing.) Or maybe they wouldn’t, and I am the perpetually naive one, startled at folks’ willingness to commodify whatever they can—friendships, loves, deaths, memories—however they can.

Maybe it is because my head is already full of all these story possibilities that most of the books I have been reading register as a dull muttering in my brain. But a few sing, and those are the ones that remind me that wading through all the lackluster pitches is worth it because occasionally, something remarkable is hiding in there, and finding it means something new might come into the world.

Entries in the dream ledger:

GEOLOGIC LISTENING by Deborah Stratman and Sukhdev Sandhu. Reading this felt less like finding a wonderful stone and more like trying to walk a mile with a pebble in my shoe. This slim little book compiles a few oppressively overcooked, overthought essays on the theme of Deborah Stratman’s films and the ineffable mystery of rocks, including a real groaner by a media studies person, a mortifyingly pretentious round-table discussion among artists, and a conversation that is mostly an exchange of flatteries between Helen Gordon and Hugh Raffles, whose work I do, actually, love. (I wrote about his mesmeric BOOK OF UNCONFORMITIES here.)

GREENGLASS HOUSE by Kate Milford. I picked this up to read before I put it out for Hugh to find; it’s a charming enough yarn about an adopted kid in a gloriously ramshackle mansion/smugglers’ inn over Christmas and the unexpected appearance of a passel of unexpected secretive guests who are all, of course, linked by a mystery. Reading it, I noticed a pattern I’ve been picking up on in newer children’s books, where characters present more like a diagnosis pulled inside out into a combination of behaviors and situations and less like actual, gloriously complex human beings. While it is heartening that authors are striving for representation, there is something distressingly reductive about chasing it this way instead of embracing the messiness of real humanity.

MY SEARCH FOR WARREN HARDING by Robert Plunket. A madcap 1980s-era tale loosely riffing on Henry James’s THE ASPERN PAPERS about the escalating hijinks of Elliott Weiner, an unscrupulous presidential scholar on the make who thinks he has a lead on Warren Harding’s reclusive long-lost lover, who is potentially hoarding a trove of salacious letters from the one-time commander in chief (“the shallowest President in history”) in her crumbling Hollywood Hills mansion that could make Weiner’s career. Funny, with a bitter bite.

TO ANYONE WHO EVER ASKS: THE LIFE, MUSIC, AND MYSTERY OF CONNIE CONVERSE by Howard Fishman. In August 1974, when she was 50 years old, Connie Converse loaded her Volkswagon Beetle, drove away from her home in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and was never seen again. She left behind a meticulously organized filing cabinet in her brother’s garage that held neatly indexed copies of her letters, professional projects, and creative pursuits, including unfinished novels, musical compositions, and a collection of songs. The songs, which were recorded in the 1950s at a house concert in Long Island, are what kept her from total obscurity—through a wild series of chances, they surfaced in the early 2000s, leading to the release of an album that has become a cult classic, additional works from her archive, and this biography. Fishman is an obsessive and dutiful biographer; he cares deeply about the art she made and is trying to understand who she was. Maybe the weight of that conscientiousness is why I found this book to be a frustrating read—too much explanation, too little historical awareness, too much wild grasping. Maybe she was a hoax! Maybe she was queer! Maybe there was abuse! Maybe there was incest! Maybe she was neurodivergent! Maybe she was one of the first singer-songwriters! (An assertion that seems to depend on defining “singer-songwriter” pretty narrowly.) Maybe she was better than Dylan! (Perhaps the epitome of useless comparison.) This kind of flailing, shoving ambiguities and unknowns into labeled boxes, reveals more about the writer’s conceptual limits than the subject’s experience of life. Fishman is very heavy in his sympathy for Converse as an exemplar of the many brilliant someones who never get the big break. But I kept thinking, my dude, have you never read Middlemarch?!

Her finely touched spirit had still its fine issues, though they were not widely visible. Her full nature, like that river of which Cyrus broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth. But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.

Or even Wallace Stegner?

Talent lies around in us like kindling waiting for a match, but some people, just as gifted as others, are less lucky. Fate never drops a match on them. The times are wrong, or their health is poor, or their energy low, or their obligations too many. Something. Talent, I tell him, believing what I say, is at least half luck. It isn’t as if our baby lips were touched with a live coal, and thereafter we lisp in numbers or talk in tongues. We are lucky in our parents, teachers, experience, circumstances, friends, times, physical and mental endowment, or we are not.

Unfulfillment *is* the human condition. Almost no one gets the chance to truly share what is in them with the world—most of us are just cobbling an existence together the best we can, out of what’s near to hand—and when opportunities come along, there are usually limits and disappointments, and even when you do manage to create something extraordinary, well, life rolls on. (See: Robert Plunket.) Converse’s life and work is well worth close attention, which Fishman offers, but I couldn’t help thinking that a more creative, less straightforward approach to writing about it, especially given the volume of written matter she left behind, might have yielded a richer, deeper book.

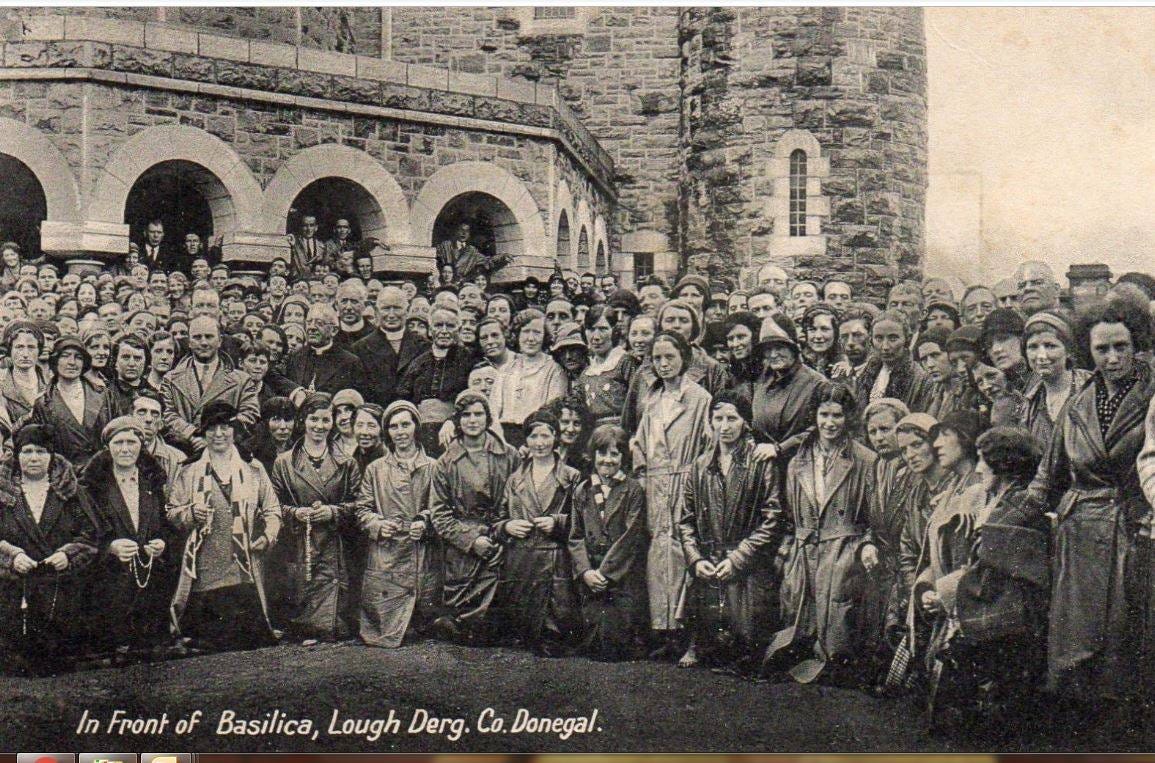

STATION ISLAND by Seamus Heaney. Gosh, I love Seamus Heaney. Attending a poetry reading he gave in Dublin was a peak life experience; I had only the dimmest notion of who he was at the time (I think he had just won the Nobel Prize, lol), but listening to him speak was like being given the momentary ability to see that the words I already knew could be bent into other, more revelatory languages. (Categorically epic!) The second section of this three-part 1984 poetry collection, Heaney’s sixth, is a poem in 12 stanzas set on Station Island, a pilgrimage site in Lough Derg, County Donegal, also known as St. Patrick’s Purgatory—sometime in the fifth century, God supposedly showed St. Patrick the entrance to hell in a cave on the island, and ever since it has been a holy site. For centuries, barefoot seekers have journeyed to the island for three days of prayer and fasting. Heaney made the pilgrimage himself more than once, and in this poem, as he moves through the stations, the shades of people he has known appear to him, including victims of the Troubles. Heaney, who was born in Northern Ireland, had left Belfast for Dublin in the mid-70s, as the conflict was intensifying, and was living part-time in the U.S. when he wrote these poems. They are shadowed by a sense of culpability, by what is owed to those left behind. I read them after I watched “Once Upon a Time in Northern Ireland,” a harrowing and extraordinary oral history of the Troubles that illuminates the sobering fact that peace is not easy or steady but a choice that people have to make together, day after day, knowing that some wrongs will never be redressed.

AN ELEMENTAL THING by Eliot Weinberger. If the devil came to me and said, okay, Stephanie, give me your eternal soul and you’ll write like Eliot Weinberger, I might take the deal. (Equally tempting: the mind/literary gifts of Susan Howe.) Anyway, this is one of the books I reread whenever I need to escape the crescendoing mediocrity of content; it is beauty and strangeness and rest and unease and erudition and morality and curiosity and wonder and sad rhinoceroses. I like to read one of his pieces before bed and hope it shapes my dreams.

*

Currently reading:

SHELLEY:THE PURSUIT (still); THE GEOGRAPHY OF THE IMAGINATION; THE NATURE BOOK.

Bookmarked:

“The Hortus Conclusus of Barbara Baum;” “The Case Against Children.”

Blogged:

Odds and ends / 1.29.2024; pretty pink things/ a billet-doux; dressing like a Rothko painting.

*

Images:

Charles Sheeler, “Geraniums, Pots, Spaces.” 1923, The Chicago Museum of Art.

Stereoscopic images of Martian rocks.

Connie Converse, photographed in New York City in June, 1958.

Pilgrims at St. Patrick’s Purgatory/Station Island in the 1920s, via the Donegal County Museum.

Ah, what a pleasure to discover your presence on Substack!!! Going to devour your archives. Really enjoyed your review of the Stratman book, ran into the book release and went to Last Things subsequently at Anthology. And was utterly transported! By that film and the two shorter ones it was paired with. The book sounds pretentious but the film is full of cosmic wonder, mystery and poetry. I love when scientists sound poetic (and poets sound scientific) 🤍🪐