One Friday in October, after dinner, we drove to the lake to look for the Northern Lights. They were barely discernible to our eyes—the faintest cast of green and red—but the camera trapped the light.

Standing on the crumbly strip of city beach, the wind in my face, I heard the water washing against the concrete barrier, I saw flashes of distant faces, the other people scattered up and down the broken shoreline, illuminated intermittently by the blue light of phones, all of us looking hard into the dark, all of us aware, for just a moment, that we were standing amidst strange, fiery, near-invisible energies.

Now, here we are, standing in another broken place, looking into a different sort of dark.

Over the summer, I read quite a few books, and I meant to write about them here. Maybe I will, but there are three that I keep thinking about.

Derek Jarman, MODERN NATURE. You may have seen this image somewhere: a small austere house, rectangular and low, black, with two windows staring yellow, set in a field of gravel improbably tufted with flowers. Depending on the angle, a power station appears in the background. This is Prospect Cottage, the Dungeness home of the artist, poet, and filmmaker Derek Jarman. He bought it as a rundown Victorian fisherman’s hut after he was diagnosed with H.I.V. in 1986, and spent most of the rest of his life there, hauling in buckets of dirt to sink into the shingle, planting poppies and sea kale and bugloss and borage and roses that somehow survived in this stony, salty place. He filled the house and garden with art from friends and things he found on the beach; part of John Donne’s poem “The Sun Rising” runs along the house’s exterior cladding. This book is a chronicle of his time there and work in the garden, as well as his life before it; it is extraordinary. First, because it is a document of his mind. Jarman had the sort of brutally deep education in Western classics that more or less vanished somewhere in the middle of the 20th century and a relentless appetite for culture, learning, and thinking, and this suffuses every line he writes. It is like standing in a sea wind: bracing, challenging, energizing. Second, because it captures time in two dimensions, both Jarman’s own shifting feelings and experiences, as he lives in the uncertainty and doom that was an H.I.V. diagnosis in the 1980s, when so much was still unknown and fear was running riot, but also the broader time, the TV programs and the politics and simply the habits of being. All books are products of their time but they are often sloppy vessels; this is not. Maybe because Jarman was very aware that his time was limited and precarious; throughout the book, friends and acquaintances die. No one really knows what to expect. But he hauls dirt to the garden. He tries new varieties of rose. He gets aggravated by idiocy and ignorance and petty annoying things. He reads and walks on the beach. His friends are there for him (Tilda Swinton shows up for him again and again, and then there is the astonishing devotion of Keith Collins, Jarman’s great platonic love.)

And Jarman keeps dreaming.

Dreamt last night I held a bowl of the rarest jade, the colour of honey with a sage green iridescence. The bowl of precious stones was threatened by a thief. I preserved it through terrible trials, assailed by the demon thug intent on stealing it. He curled round me ceaselessly, like a crab, with switchblade claws; then suddenly it was over. He deflated like a balloon, disappeared like a little Michelin man with a gasp of rushing air.

Otto L. Bettmann, THE GOOD OLD DAYS—THEY WERE TERRIBLE! This book has the aesthetic of a title destined to live sandwiched between old copies of Reader’s Digest, Ripley’s Believe It or Not, and Chicken Soup for the Soul in a jumbled rack near the toilet. I found it at a book sale in June and bought it for $.50, mostly because I was amused by the chapter subheadings:

The Kitchen: A vale of toil

Farm Women: Draft horses of endurance

Farm Children: They lead a life of numbing blandness

Loneliness: The West was haunted by loneliness, and its twin sister, despair

Those are all sections from the chapter on rural life; Bettmann also covers air, traffic, housing, work, crime, food and drink, health, education, travel, and leisure. When I sat down to read it, though, my amusement gave way to fascination and admiration. In 1935, Bettman fled to the U.S. from Germany, where he had been director of the state art library in Berlin. In New York, he assembled what would become the Bettman Picture Archive, a three-million-image resource for “publishers, educators, ad-men and the audio-visual media.” He pulled together this book in 1974, at the rump of the Nixon era, drawing from images and news clippings in his archive to offer a corrective to what he saw as the “benevolent haze” obscuring the United States’ collective historical memory of the late 19th and early 20th century:

I have always felt that our times have overrated and unduly overplayed the fun aspects of the past. What we have forgotten are the hunger of the unemployed, crime, corruption, the despair of the aged, the insane and the crippled. The world now gone was in no way spared the problems we consider horrendously our own, such as pollution, addiction, urban plight or educational turmoil. In most of our nostalgia books, such crises are ignored, and the period’s dirty business is swept under the carpet of oblivion. What emerges is a glowing picture of the past, of blue-skied meadows where children play and millionaires sip tea.

If we compare this purported Arcadia with our own days we cannot but feel a jarring sense of discontent, a sense of despair that fate has dropped us into the worst of all possible worlds. And the future, once the resort of hopeful dreams, is envisioned as an abyss filled with apocalyptic nightmares.

The book is simple and brisk, with a spread dedicated to each subchapter summing up just how wretched things were in any one specific dimension of ordinary American life, illustrated with photographs, etchings, and newspaper quotes from the time. These horrors build and build, illuminating a country with city streets full of shit, air full of smoke, shoddy housing, public beaches with bloated animal corpses, milk adulterated with chalk, children beaten by schoolteachers and maimed at factories, workers driven to despair, corrupt officials at every level of government, and the cruelties of so-called justice, enacted through inhumane punishments and lynching. While many of the problems Bettmann discusses are still with us in altered forms, his point holds: Overall, things are so much better—startlingly, shockingly better. I found myself thinking that if I could jump back to 1900 and talk to someone then, they might well have no hope that anything would ever change. And yet, so many seemingly impossible things came to pass because people did try, and kept trying.

For anyone tempted by the notion that the past was somehow better, in any way, shape, or form, it is a clarifying read.

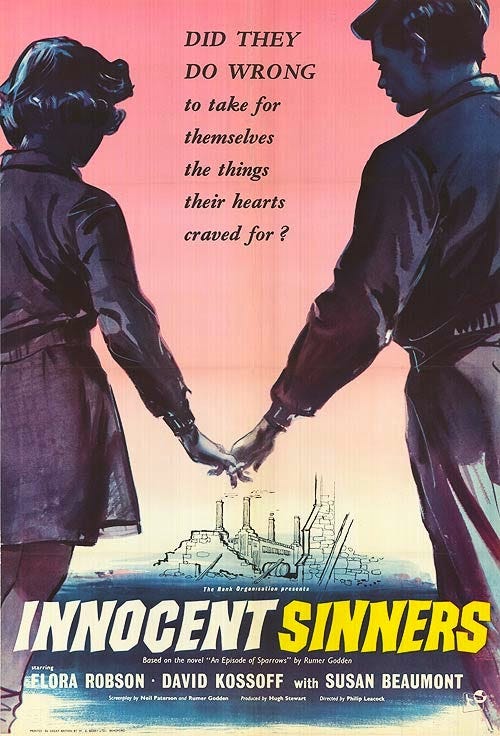

Rumer Godden, AN EPISODE OF SPARROWS. I had read exactly two other books by Godden—a charming slight one about a mouse and a dollhouse and a peculiar, memorable one about three sisters pinioned like specimen butterflies by the social stratifications of British colonial culture. Neither one prepared me for this. Octopuses have three hearts and hagfish have four; I am not sure how many this story has—at least two, but maybe five. One is Lovejoy Mason, a little girl growing up between the cracks of society, suddenly and furiously possessed by the impulse to create a garden in her ratty, post-Blitz London neighborhood. But there is Olivia, middle-aged and muddled, smothered by the efficient morality and complacent prosperity of her sister, Angela, but reaching for some way to make her life make sense. There is Sparkey, small and runny-nosed and bony-legged, and Tip, who can’t help himself from helping. There is Vincent and his empty restaurant, and his wife, Mrs. Crombie, trying to make it work. There is a miniature rosebush. And then there are the plates. I don’t think I’ve ever come across another scene in literature where a plate made me cry.

It’s a beautiful, subtle, richly observed story about the possibility and impossibility of change and compromise and love.

"I sometimes think," said Olivia, "from watching, of course, because I am not experienced, I think experience can be a—block." Again it was clumsy, but she knew what she meant.

"And why?" asked Angela, amused.

"Because if you think you know, you don't ask questions," said Olivia slowly, "or if you do ask, you don't listen to the answers." Olivia had observed this often. "Everyone, everything, each thing, is different, so that it isn't safe to know. You—you have to grope."

*

Currently reading: THE BOOK AGAINST DEATH, THE ANNUAL BANQUET OF THE GRAVEDIGGER’S GUILD.

Bookmarked: GASLIGHT, THE ELEVEN ASSOCIATES OF ALMA-MARCEAU, FAIRY TALES FOR THE DISILLUSIONED, PARTISAN OF THINGS.

Blogged: a shell collection / odds and ends 9.6.2024 / hounds of love / a handful of apples / circling the sun / trouble / uncanny materiality / protect the vulnerable and speak the truth

*

Images:

Photograph of Northern Lights over Lake Erie by me.

Photograph of Prospect Cottage by Howard Sooley.

Trailer for “The Garden,” by Derek Jarman, 1990.

Mary Harris, better known as Mother Jones, surrounded by striking child mill workers, via the Library of Congress.

Movie poster for “Innocent Sinners,” a movie based on AN EPISODE OF SPARROWS.

I just borrowed Modern Nature from the library on your recommendation, can't wait to start!

What a gorgeous photograph you took, Stephanie! I gulp up anything by Jarman...