Charles Dickens, LITTLE DORRIT: When I was in 7th grade, one of my English teachers told me I wrote like Charles Dickens, and I was so insulted. (In that benighted era, Dickens had not yet been Peaky Blinder-fied.) Of course, I had not read much Dickens, mostly Pickwick and only because the March sisters were obsessed, and David Copperfield, which I enjoyed even as the Murdstones made my skin crawl. I had definitely not read the greatest Dickens (top three: Bleak House, Great Expectations, and Our Mutual Friend). Either way, we were both deluded: me, because Dickens is phenomenal and I should be so lucky, and my teacher, because no 13-year-old writes like CD—no one writes like him at all, really, though his shadow streaks through so, so many works in English (not least Roald Dahl, who is like Dickens with kindness excised and cruelties and folly concentrated to bouillon, mixing ghastly abusers and innocents with witches, quirky chocolatiers, and giants).

Originally, I only read Little Dorrit because my favorite professor gave me a copy as a graduation gift, and it opened the door to Dickens for me. The premise did not seem especially promising to me then: a girl born in a debtor’s prison may be somehow be tangled up in a dying man’s mystery, the only clue a memento inscribed “Do Not Forget” stashed in a pocket watch that he trusts his middle-aged son to deliver to his estranged wife. This is the fuel that powers a classically Dickensian Rube Goldberg-style whiz-bang contraption plot, churning inexorably through 800-some pages to an appallingly neat conclusion. There is Victorian moralizing. There is social injustice (as a kid, I did not clock how absolutely furious Dickens was at the idiocies and cruelties of his times; it’s bracing). There are windy and baggy passages, an impossibly virtuous hero and heroine, and a rotten house that symbolizes a rotten family. There are ridiculous and pathetic and funny and unforgettable characters galore, including a swaggering French murderer, a terrifying lesbian, a raging foundling, a religious zealot, a vapid family of professional bureaucrats called the Barnacles, a proto-Madoff financier, a society wife referred to as “The Bosom,” a faux-benevolent landlord and his deeply silly daughter, a hapless family of kind-hearted plasterers, an engineer with a peculiarly flexible thumb, and Pancks, the human coal ship, and this is nowhere near all. Who can ever forget sweet John Chivery?! And poor Pet Meagles, who follows her heart to wed the charming and odious Henry Gowan, illuminating in the margins how cruel an unwise marriage can be. Taken all together, it is glorious. There is something so satisfying in the muchness, in all of these people colliding into each others' lives—though, of course, in Dickens, the collisions are all chess moves serving the plot, which here traces the stories of two people burdened by uniquely awful families: Amy Dorrit, consigned through duty to serve the whims and delusions of her foolishly status-obsessed family; and Arthur Clennam, who has spent his life under the thumb of his horrifying mother, who believes God ordains all that she does, and who is trying to figure out what her cruelties may have cost him.

It all makes most contemporary literature feel laughably spare in comparison, though maybe it is a flawed comparison given how mediums have changed where certain stories get told. In a recent New Yorker hand-wringer on the state of college humanities majors, Stephen Greenblatt mused on the literariness of prestige TV, and Dickens has a showrunner’s sensibility, spinning out his story threads, giving each member of the cast choice bits while making things happen. (This is probably why so many of his books still keep getting made into shows and movies—there's a particularly good version of Little Dorrit starring Tom Wambsgans.) Even so, reading is a different pleasure than watching, and there is a real magic in experiencing how Dickens uses words—mere words!—to make his teeming worlds come to life in your mind’s eye. I might reread Bleak House next.

Italo Calvino, MARCOVALDO: I ration Italo Calvino books because I love them so and it comforts me to know there is still more of his I have yet to read but it was time to break the glass on a new one. These 20 transporting short stories—some only a few pages—tell of Marcovaldo, who lives with his wife and too many children in a grubby industrial town somewhere in Italy and exists perched on the edge of the real and the fantastic, and the bemusing ways his good ideas and lucky breaks inevitably lead to disaster and confusion.

Shola Von Reinhold, LOTE: This tasty bit of literary confectionery centers on the transfixions of Matilda, a Black researcher enraptured by the decadent pleasures of the Bright Young Things, particularly the glimmering traces left behind by Hermia Druitt, a Black woman who was a poet, possible resurrector of a lost cult of luxuries, and seemingly unforgettable, except that she has almost disappeared from the archive. Then Matilda is accepted to a residency of ascetic “thought artists” who seemingly stand in opposition to everything Druitt represents yet are somehow mysteriously and inextricably bound to her (non)existence. It’s heady and gossipy and poppily academic and feels very much in dialogue with the work of Saidiya Hartman in its imaginings of the possibilities of historical gaps in conjuring different ways to exist and of fiction as the necessary net to catch the quicksilver lives the archive cannot hold.

Eleanor Catton, BIRNAM WOOD: An earnest, semi-guerilla lefty gardening operation in New Zealand led by two passive-aggressive women/friends, its rogue co-founder-turned-citizen journalist, and a pair of newly knighted Baby Boomers get tangled up in the extractive machinations of a psychotic libertarian billionaire. Disasters ensue! After deeply enjoying THE LUMINARIES, Catton’s ambitious and entrancing astrologically-patterned sprawler about New Zealand frontier life, I was surprised to discover that her literary ambitions have taken a Michael Crichton-esque turn. (To be fair, this book was a lot less thrilling and grimily satisfying than I remember Crichton books being—the action burbles along, the end is a chaotic mishmash, and I never got the satisfying illusion that somehow reading this hipped me to anything, the way Jurassic Park sexed up chaos theory back in the day.) Could be a decent airport layover/beach read novel for the sort of person who describes themselves as center-left, still complains about millennials, secretly fetishizes billionaires, and reads The Atlantic.

E. Nesbit, THE ENCHANTED WOOD: Deep in the forest is a massive old tree. You’ll only find it if you follow the elves. If you climb it (and the elves will tell you not to do it, because it is dangerous), the Angry Pixie will yell, but keep going. Dodge the soapsuds Dame Washalot empties from her door, and avoid waking the somnolent and ever-cranky Mr. Whatziname. Silky the Fairy might offer you cakes, and at Moon-Face’s place, you’ll find a slippery-slide to whirl you all the way down through the center of the tree back to the ground, but don’t go just yet, because the top of the tree will take you to wondrous places, strange lands that shift with the clouds and obey their own peculiar logic, like the land of Birthdays, which can only be visited when it is someone’s birthday, and where all the birthday child’s wishes will come true. Don’t stay too long, or you might get carried you away. I read this on the recommendation of my seven-year-old; the writing is just serviceable, but who cares, because the imaginings enchant.

Currently reading: Lucy Ives, LIFE IS EVERYWHERE (hoping it clicks into something more interesting than a grab bag of tricks soon because rn it is mostly clevernesses wearing thin).

Bookmarking: DIAMOND DORIS, LIVES OF THE SAINTS, TWO SERIOUS LADIES (thanks to this review), PIRATE ENLIGHTENMENT

Blogging: odds and ends / 4.11.2023; odds and ends / 3.17.2023; imaginary outfit: a day-and-a-half knocking around new york city

*

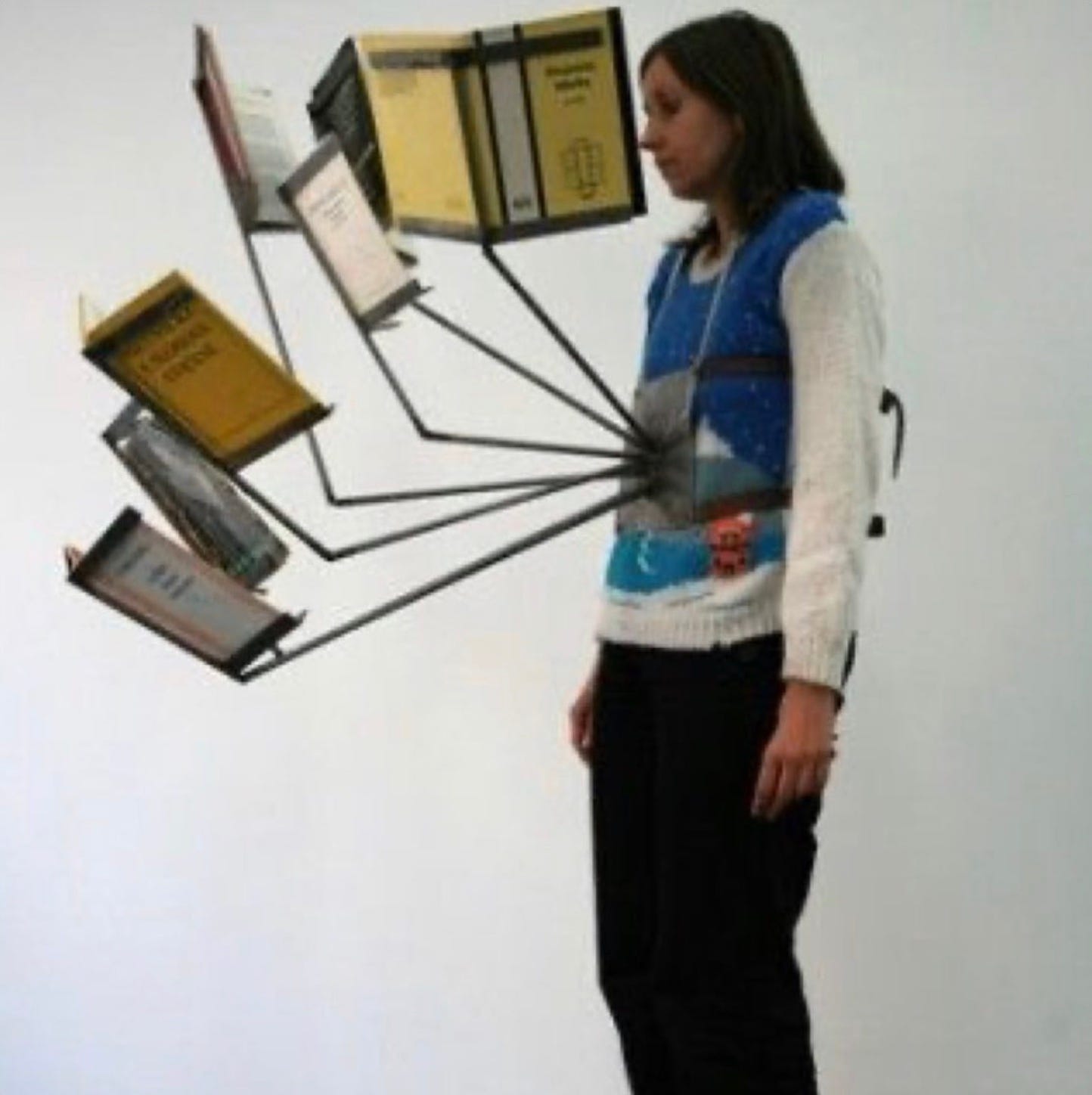

Image found via Worms Magazine. I do not know what it is, but I love it.

"Could be a decent airport layover/beach read novel for the sort of person who describes themselves as center-left, still complains about millennials, secretly fetishizes billionaires, and reads The Atlantic. " Ha, amazing.