Friends don’t let friends get lost in fairy rings.

I have been amusing myself lately thinking how choosing books to read can be like deciding what sort of cookie to bake. (I love to bake and I love to read, so this is just my lazy brain drawing a line between two ongoing preoccupations.) In cookie-land, I am often drawn to recipes with fussy, fiddly steps, like toasting flour blends and browning and re-chilling butter before it is creamed. They promise something new in a familiar format, even if they rarely deliver. Then, there are the hype recipes. Many involve screaming adjectives—THE BEST, LIFE-CHANGING, TRIUMPHANT, WORLD PEACE. Some defy adjectival description; they are simply “the” cookie. It’s all tempting (and manipulative). But who doesn’t want to have their life changed by something as accessible as a cookie—or a book? Even though I should really know better by now—most of the time, I end up with something that is merely fine.

Sometimes, though, I don’t want to mess around with aging dough, banging pans,* or shelling out money on ingredients that will languish in the flour-dusted recesses of my pantry until they expire. What I want is a pack of Voortman’s wafers—delicious, easy, reliably perfect—or the reading experience equivalent. So I picked up two books that I hoped would be crisp and tasty.

Hunting for flavor!

Heather Fawcett, EMILY WILDE’S ENCYCLOPEDIA OF FAIRIES. Sadly, this one turned out to be a SnackWell’s. When I was a kid, packets of low-fat SnackWell’s cookies often appeared at classroom parties for room mothers and teachers to guiltily nibble while hyper preteens slammed silvery pouches of Capri Sun and inhaled frosted box brownies. They looked like a real cookie but were mostly strange textures—a dry crumbliness that became a sort of vaguely vanilla chemical mouthpaste. Anyhow: This tale of Emily Wilde, a crotchety young British lady academic and her professional rival/inevitable/implausible love interest venturing into a remote faux-Icelandic village to do fieldwork on various malevolent fairies ca. 1900 struck me as a synthetic amalgam of other books, specifically Elizabeth Peters’ amusing H. Ryder Haggard-esque Amelia Peabody series and Susanna Clarke’s inimitable and uncanny JONATHAN STRANGE AND MR. NORRELL. Though it appears to have been engineered to meet the taste expectations of many readers, for me, key ingredients were left out of the mix. (I find a dash of grimily plausible reality powerfully enhances depictions of magic, just like a splash of coffee intensifies the flavor of chocolate.)

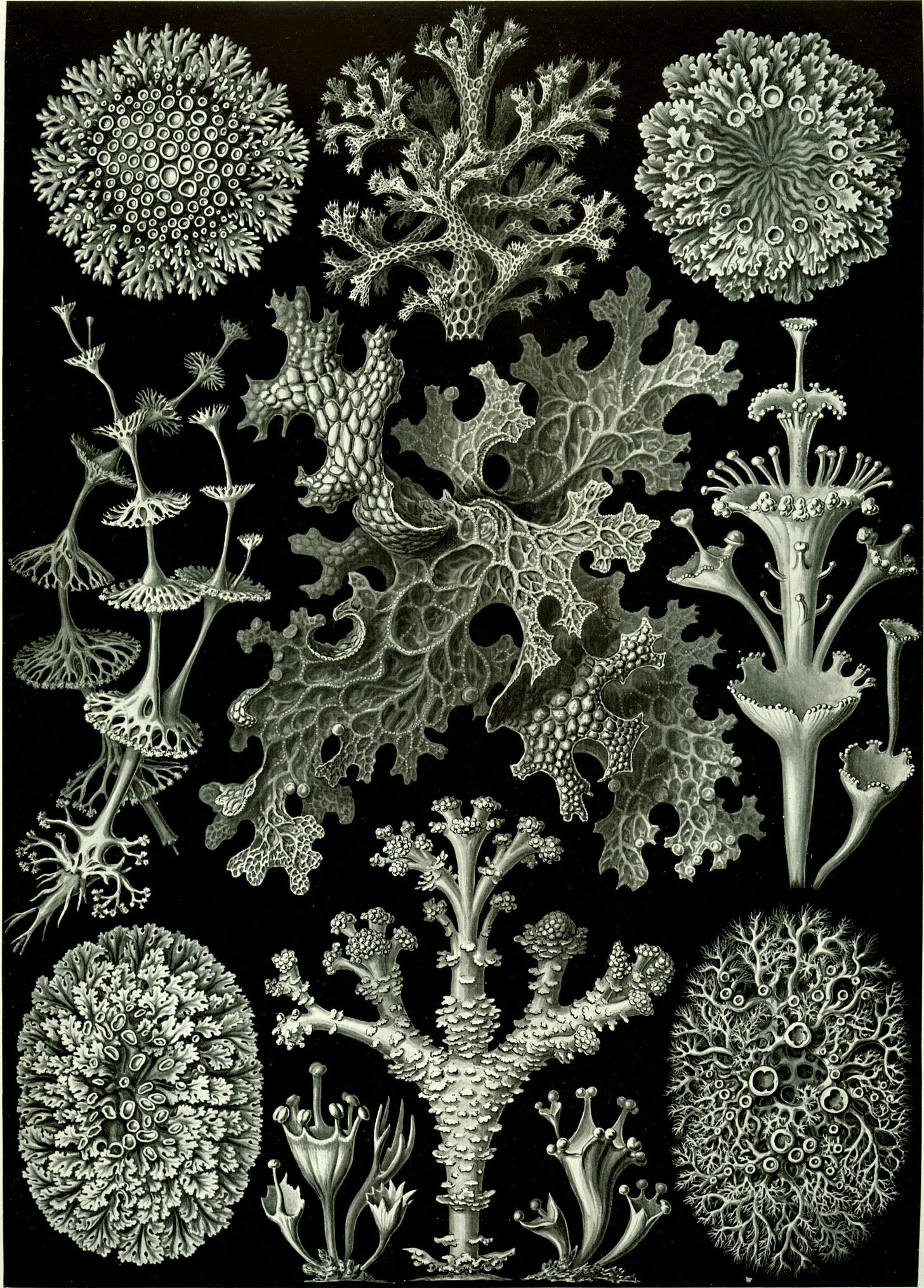

John Wyndham, TROUBLE WITH LICHEN. This was more like it. Diana Brackley is brainy, beautiful, pragmatic young woman who troubles her family and teachers with her unsettlingly direct insights about the societal hypocrisies flourishing around her in 1950s-era Britain. After an encounter with the brilliant biochemist Francis Saxelby, Diana becomes a biochemist, too, landing a job at Saxelby’s innovation-minded firm. There, they simultaneously discover the remarkable property of a rare lichen, and while Saxelby is paralyzed by its implications, Diana springs into action, using a wellness empire (ha) to set in motion a long-range plan to empower women to reshape their lives—and the world. (Sidebar: GOOP should look into lichens.) When the secret comes out, Diana and Francis have to reckon with what they’ve unleashed. It’s fun, fizzy, deceptively clever sci-fi of its time asking still-sharp questions beneath its standard-issue love story.

Nice, non-troublesome lichens ... or are they?

*These are worth banging a pan for, though.

Currently reading: LIFE IS EVERYWHERE (still), CATHERINE DE MEDICI: RENAISSANCE QUEEN OF FRANCE (still), and THE LINE OF BEAUTY.

Bookmarking: EMOTIONALLY DURABLE DESIGN: OBJECTS, EXPERIENCES AND EMPATHY

Blogging: Odds and ends / 5.9.2023

*

Images:

“Plucked from a fairy circle.” From Wirt Sikes’ British Goblins: Welsh Folk-lore, Fairy Mythology, Legends and Traditions, pp. 74 (1880). London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington.

Julia Child in Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1978. LYNN GILBERT/CC BY-SA 4.0

Ernest Haeckel, Kunstformen der Natur (1904), plate 83: Lichenes.